Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

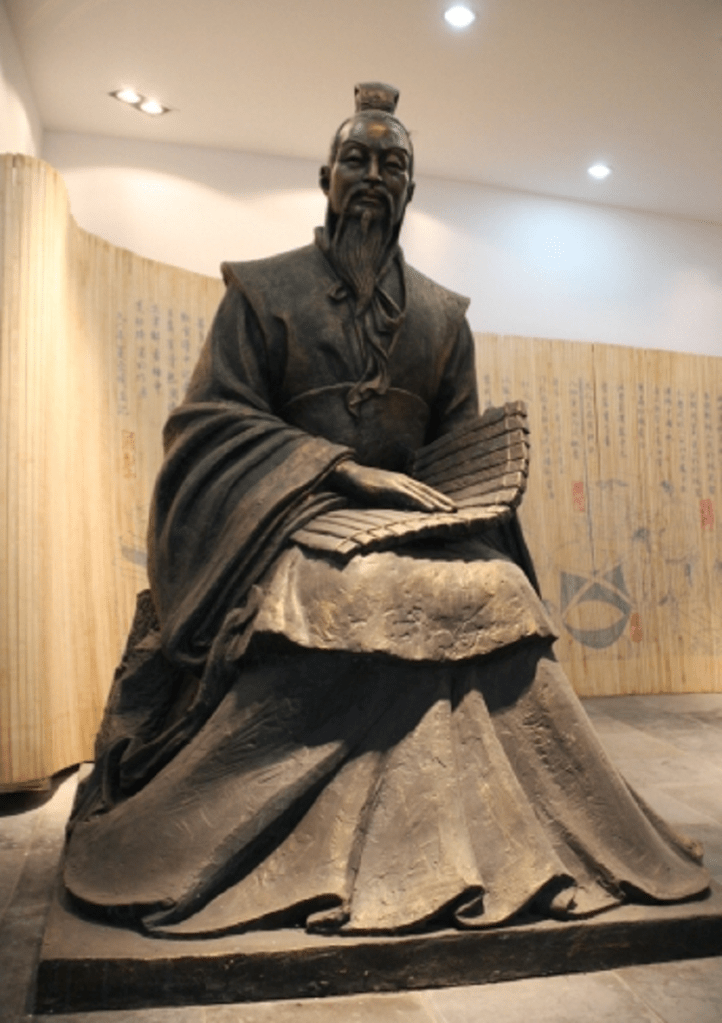

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 11 Scroll 19 (continued)

The 1st year of Emperor Wu’s Yuan’shou Era (122 B.C.)

In the winter of October, the Emperor journeyed to Yong to perform sacrifices at the Five Altars in honor of the Five-Deities. During the ceremony, a mythical creature with a single horn and five hooves was captured. The rite officials, in their memorial, declared, “In response to your Majesty’s solemn ceremony, Heaven has bestowed a unicorn, likely the legendary Qilin.” The unicorn was offered in sacrifice at the Five Altars, and an ox was added to the roast fire at each altar.

After some time, the officials further expounded on the omen, interpreting the event as a celestial sign of unique importance. They declared, “This rare occurrence—capturing a mythical beast with a single horn—reveals that Heaven wishes for the reign to be designated with auspicious titles, rather than mere numerical sequences. The first era of your reign shall be named ‘Jian’ [Establishment], the second ‘Guang’ [Light], following the appearance of the comet. As for the current era, it shall be named ‘Shou’ [Hunting], due to the appearance of the unicorn during the ceremonial rites.”

The Prince of Jibei, discerning in these signs that the Emperor was poised to undertake the Feng-Shan ceremony, proposed placing Mount Tai and its surrounding regions directly under the control of the Han Household. The Emperor accepted this proposal and compensated the Prince with lands from other counties.

Prince of Huainan, Liu An, and his retainers, including Zuo Wu, plotted day and night, deliberating over rebellion. They studied maps and devised strategies for troop movements, planning their routes for the march. Meanwhile, various envoys arrived from Chang’an, bearing conflicting reports. Some brought false tidings, saying, “The Emperor has no male heir; the Han court is in turmoil.” Upon hearing this, Prince Liu An was momentarily overjoyed. However, other envoys contradicted this, stating, “The Han court is well-governed, and the Emperor has a male heir.” Enraged, the prince dismissed these claims as lies.

In his anger, the Prince summoned the Gentleman of the Household, Wu Bei, to discuss the matter of rebellion. Wu Bei, ever cautious, spoke, “How could Your Majesty speak words that would bring ruin to the state? I foresee a dark future: thorns within the palace and morning dew soaking our clothes.” The prince, infuriated by this warning, casted Wu Bei‘s parents into prison.

After three months, the Prince summoned Wu Bei once more. Wu Bei, in his counsel, said, “In the past, the House of Qin ruled with ruthless cruelty and excess, leading six or seven out of ten households to desire rebellion. Amidst this turmoil, Emperor Gaozu rose to power, becoming Emperor. He was known as one who exploited the weaknesses of the Qin, seizing the opportunity brought by their downfall. Now, Your Majesty, having witnessed how easily Emperor Gaozu acquired the world, Have you not considered the recent history of the Principalities of Wu and Chu?

“The Prince of Wu governed four commanderies, with a wealthy state and a large population. He planned meticulously, yet failed. He raised troops to march westward, but was defeated at the principality of Liang. Forced to flee eastward, he perished, and his ancestral sacrifices ceased. Why? Because he defied the natural order, failing to understand the proper timing.

“At present, Your Majesty’s army, though mighty, is but even a tenth of the power of the Principalities of Wu and Chu. The world is at peace now, thousands of times more so than in the days of the Wu and Chu Uprisings. Your Majesty, if ignoring my counsel, will forsake a monarch ruling thousands of chariots and face the decree of self-destruction, dying before all the courtiers in the Eastern Palace.”

The prince, upon hearing these words, rose and left, weeping.

The Prince had an Ishmael son named Liu Buhai, the eldest of his progeny, yet he was not favored by the Prince. Neither the Queen nor the Crown Prince of Huainan regarded him as a son or a brother. Liu Buhai, in turn, had a son named Liu Jian, a youth of remarkable talent and vigor. Liu Jian, however, harbored a deep resentment toward the Crown Prince of Huainan(Liu Qian) and secretly accused him of conspiring to assassinate Duan Hong, the Han envoy and Commandant of the Capital Guard. The Emperor, upon learning of this, handed down this case to the Justice Minister for investigation.

The Prince, troubled by the affair, sought a resolution. Once again, he turned to Wu Bei, asking, “Do you think it was wise for the Prince of Wu to raise troops against the Han Empire, or not?”

Wu Bei replied, “No, it was not wise. I have heard that the Prince of Wu deeply regrets his actions. I hope, Your Majesty, do not repeat the same mistake, and regret as the Prince of Wu did.”

The Prince said, “What did the Prince of Wu truly understand of rebellion? There were usually more than forty Han officers passing through Chenggao each day. Now, I have sealed off Chenggao, secured the strategic confluence of the Three Rivers—Yi River, Luo River, and Yellow River—and rallied the forces east of Mount Xiao. By such actions, Zuo Wu, Zhao Xian, and Zhu Jiaoru are confident the plan has nearly a ninety percent chance of success. Yet, you alone foresee misfortune and no happy ending. Why? Do we truly have no chance, as you claim?”

Wu Bei countered, “If there is no other way, I offer a foolish plan. At present, the feudal lords harbor no rebellious intentions, and the common people bear no grievances. We can forge a petition, purportedly from the Chancellor and the Grand Master of the Censorate, calling for the relocation of influential and wealthy individuals from various commanderies to Shuofang. This would also involve increasing the recruitment of soldiers and setting an urgent assembly deadline. Furthermore, we could fabricate sentences to arrest the crown princes of the principalities and favored courtiers of the feudal lords. This would stir resentment among the people and instill fear among the monarchs. Then, we could send skilled lobbyists to persuade them. Perhaps, on a lucky day, we might achieve a ten percent success rate.”

The Prince said, “This plan is feasible. However, I do not believe we would need to resort to such extremes.”

Thus, the Prince crafted an imperial seal and seals for the Chancellor, Grand Master of the Censorate, generals, military officers, officials holding 2,000-picul rank, as well as seals for the nearby prefects and commandants. He also forged the insignia and scepters of the Han envoy. His intention was to falsely implicate someone and send them running westward to seek refuge under the Grand General Wei Qing. On a chosen day, troops would be mobilized, and the Grand General would be assassinated.

Additionally, he remarked, “Among the prominent ministers of the Han court, only Ji An values straightforward admonitions, upholds integrity, and is difficult to deceive with falsehoods. Others, such as Chancellor Gongsun Hong and the rest, are easily swayed, like drapes being removed or leaves shaken off trees.”

The Prince, desiring to deploy the local troops, feared that the Prime Minister and the officials appointed by the court, those with 2,000-picul rank, might not comply. Therefore, he conspired with Wu Bei to first assassinate the Prime Minister and the officials appointed by the court. He also devised a plan to have someone dressed as a police officer, carrying a feather message, arrive from the east and shout, “The troops of Nanyue have entered the borders!” This would serve as a pretext for the deployment of troops.

The Minister of Justice in the Han Court was ordered to arrest the Prince of Huainan. Upon hearing of this decree, the Prince conspired with the Crown Prince(Liu Qian), summoning his Prime Minister and the officials of 2,000-picul rank with the intent to murder them and initiate a rebellion. When the Prime Minister arrived, the Minister of Interior and the Commandant of the Guard of the principality failed to appear. Realizing that the death of the Prime Minister alone would bring him no gain, the Prince dismissed him, remaining hesitant and indecisive. The Crown Prince, in despair, chose to take his own life by slitting his throat, but was unsuccessful.

Wu Bei, moved by conscience, voluntarily approached the authorities and revealed the details of the Prince’s conspiracy. The authorities swiftly apprehended the Crown Prince and the Queen of Huainan, surrounded the royal palace, and identified all those within the principality implicated in the rebellion. Evidence of the mutiny was presented to the Emperor. The Emperor ordered the prosecution of the Prince’s retainers, while commanding the Minister of the Imperial Clan to oversee the investigation with the Emperor’s personal insignia. Before the Minister could reach the Prince, the latter took his life by slitting his throat. The Queen of Huainan, Tu, and the Crown Prince, Liu Qian, were executed, and all involved in the conspiracy met with punishment.

The Emperor, having acknowledged Wu Bei’s eloquence and his prior praise of the virtues of the Han, was initially inclined to spare him. Yet the Minister of Justice, Zhang Tang, asserted, “Wu Bei was the first to plot rebellion for the Prince; such a crime cannot be pardoned.” As a result, Wu Bei was executed.

Zhuang Zhu, the Attendant-in-Waiting, maintained a close relationship with the Prince of Huainan, engaging in private discussions and receiving generous gifts from him. The Emperor, hoping to pardon his guilt and spare him from execution, was opposed by Zhang Tang, who remarked, “Zhuang Zhu, as an intimate attendant, moves freely in and out of the imperial gates. If he deals privately with feudal lords, pardoning him would set a dangerous precedent.” Ultimately, Zhuang Zhu was executed publicly in the market.

Meanwhile, Prince of Hengshan, Liu Ci, submitted a memorial requesting the removal of the Crown Prince of Hengshan, Liu Shuang, and the appointment of his younger brother, Liu Xiao, as the new Crown Prince. In response, Liu Shuang dispatched his confidant, Bai Ying, to Chang’an, accusing Liu Xiao of secretly constructing chariots, forging arrowheads, and engaging in illicit relationships with his father’s concubines. In the course of capturing conspirators linked to the Prince of Huainan, officials discovered Chen Xi hiding in Liu Xiao’s residence. Liu Xiao, upon hearing of the law granting immunity to those who confess first, readily confessed his involvement with the conspirators Mei He and Chen Xi. The authorities called for the arrest of Prince Hengshan, but the prince chose to end his own life.

The Queen of Hengshan, Xu Lai, the Crown Prince Liu Shuang, and Liu Xiao were all executed in the public market, alongside all those involved in the conspiracy.

The fall of the Princes of Huainan and Hengshan brought ruin to many, implicating numerous marquises, officials with 2,000-picul rank, and other influential figures. In total, the upheaval led to the loss of tens of thousands of lives.

Leave a comment