Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Qin Book 3 Scroll 8 (continued)

The 3rd year of the Second Emperor(207 B.C. continued)

Earlier, the eunuch Chancellor Zhao Gao sought to establish absolute authority over the Qin empire but feared that other court officials might not be fully obedient. To test their loyalty, he devised a scheme. He presented a deer to the Second Emperor and said, “This is a horse.” The Emperor laughed and said, “Are you mistaken, Chancellor? You call a deer a horse?” The Emperor then asked those around him for their opinion. Some remained silent, others agreed it was a horse to appease Zhao Gao, while a few said it was a deer. Zhao Gao covertly persecuted those who called it a deer. From that point on, all the court officials were terrified of him, and no one dared to disagree with him.

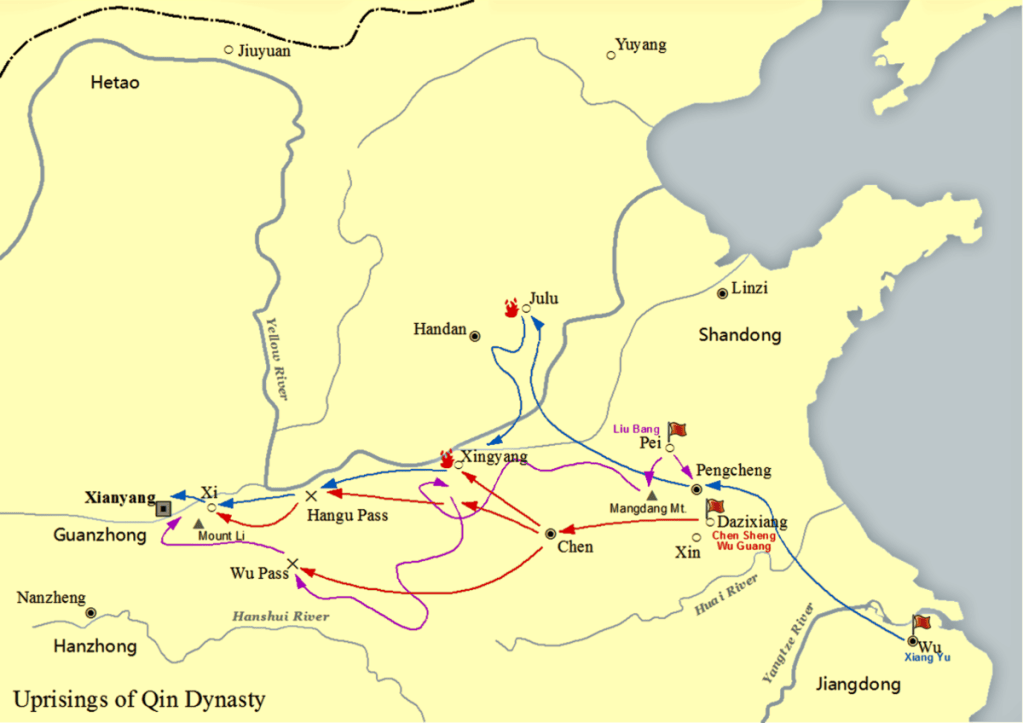

Zhao Gao often dismissed the uprisings east of Hangu Pass, saying, “They are merely burglars, not a serious threat.” However, after Xiang Yu captured General Wang Li, and General Zhang Han suffered a series of defeats, Zhang Han sent repeated requests for reinforcements. Meanwhile, many towns east of Hangu Pass rebelled against Qin officials and aligned with the other kingdoms. Generals from these kingdoms began leading their armies westward toward Qin.

In August, the Duke of Pei led tens of thousands of troops through Wu Pass, annihilating all its defenders. Fearing that his lies had angered the Second Emperor and would result in his own execution, Zhao Gao feigned illness and stopped attending court.

The Second Emperor had a troubling dream in which a white tiger bit and killed the leftmost horse of his chariot. Feeling uneasy, he sought the interpretation of a shaman, who told him, “The deity of the Jing River is the source of this trouble.” Disturbed by the dream, the Emperor began fasting and praying at Wangyi Palace, planning to appease the Jing River deity by sacrificing four white horses. Simultaneously, he sent a message reprimanding Zhao Gao for his mishandling of the eastern rebellions. This frightened Zhao Gao, who conspired with his son-in-law, Yan Le, the mayor of Xianyang, and his brother Zhao Cheng.

Zhao Gao lamented to them: “The Emperor no longer heeds my counsel. Now, he blames me in his time of crisis. I intend to depose him and enthrone Ziying. Ziying is kind and prudent, and everyone speaks well of him.” He then ordered the court security chief, Zhao Cheng, to act as an insider. Zhao Gao fabricated a story that gangsters had infiltrated the palace, and Yan Le was to send his troops inside under this pretext. As leverage, Zhao Gao also took Yan Le’s mother hostage.

Yan Le led a thousand officers and soldiers to the gates of Wangyi Palace, tying up the chief guard and the court attendants. He shouted, “Gangsters have entered the palace! Why did you stop them?” The chief guard retorted, “The palace is well-guarded at all times. How could gangsters have gotten in?” In response, Yan Le ordered the chief guard’s execution. His forces stormed the palace, firing arrows. Eunuchs and servants panicked—some fled, while others were killed. Dozens died in the chaos.

Zhao Cheng and Yan Le penetrated the inner court, where the Second Emperor was praying. An arrow struck the Emperor’s curtains, enraging him. He called for his servants, but they were too paralyzed by fear to act. Only one eunuch remained by his side. The Emperor asked, “Why didn’t you tell me the truth earlier? Now it’s come to this.” The eunuch replied, “I have survived by staying silent. Had I told you the truth, I would have been killed long ago.”

Yan Le confronted the Second Emperor, accusing him: “You are tyrannical and reckless. You’ve killed countless people without remorse, and the entire country has risen against you. What do you intend to do now?” The Second Emperor pleaded, “May I see the Chancellor?” Yan Le refused. The Emperor then begged, “I want to be a king of a commandery.” Again, the answer was no. He lowered his request: “I want to be a marquis with a fief of ten thousand households.” Yan Le still refused. Finally, the Emperor pleaded, “Let me be a commoner, living with my wife, like the other princes.”

Yan Le replied coldly, “I have orders from the Chancellor to kill you for the good of the realm. Say as much as your honor wants, I cannot report back.” He then ordered his soldiers to advance. Cornered, the Second Emperor took his own life.

Yan Le reported back to Zhao Gao, who then summoned all the court officials and royals to inform them of the Second Emperor‘s death. Zhao Gao declared, “Qin was originally a kingdom, and only the First Emperor became ruler of all under heaven, claiming the title of emperor. Now, with the six kingdoms restored and Qin’s territory diminished, it is no longer fitting to call ourselves an empire. Let us return to being a kingdom.” He then enthroned Ziying as the King of Qin, and the Second Emperor was buried as a commoner in Yichun Garden, south of Du County.

In September, Zhao Gao ordered Ziying to begin fasting and praying in preparation for a ceremony in which he would worship at the ancestral temple and receive the royal jade seal. On the fifth day of fasting, Ziying devised a plot with his two sons. He said, “Chancellor Zhao Gao murdered the Second Emperor at Wangyi Palace. Fearing retaliation from the court, he pretended to seek justice by making me king. I have heard that Zhao Gao conspired with the Kingdom of Chu to eliminate all Qin royals and divide Qin into smaller kingdoms. His plan is to kill me when I go to the temple under the guise of this ceremony. I will feign illness, and when Zhao Gao comes to force me, we shall kill him.”

Zhao Gao sent numerous messengers to urge Ziying to attend the temple ceremony, but Ziying refused. Eventually, Zhao Gao came in person, demanding, “The ancestral temple ceremony is the most important event for the kingdom. Why, as king, are you refusing to go?” At that moment, Ziying assassinated Zhao Gao in the palace where he had been fasting. He then ordered the execution of Zhao Gao’s entire family, setting an example to others.

Ziying dispatched additional troops to defend Yao Pass. The Duke of Pei intended to launch an attack on the pass, but Zhang Liang advised caution: “The Qin army is still strong, and we should not underestimate them. We should set up banners and flags on the mountains to create the illusion of a larger force, then send lobbyists Li Yiji and Lu Jia to negotiate with Qin’s generals, offering them incentives.” The Qin generals, as predicted, were open to negotiations. The Duke of Pei was prepared to finalize the deal when Zhang Liang suggested another approach: “Though the generals may be ready to switch sides, their soldiers may not follow. Now that their guard is down, it is better to strike.”Following this advice, the Duke of Pei led his troops around Yao Pass, cleared Mount Kuai, and routed the Qin army south of Lantian. After taking Lantian, they fought another battle north of the town, decisively defeating the Qin forces again.