Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 16 Scroll 24 (continued)

The 1st year of Emperor Zhao’s Yuanping Era (74 B.C. continued)

Huo Guang, directing that memorials of state be submitted to the Eastern Palace, judged that the Empress Dowager should be instructed in the Confucian classics. He commanded Xiahou Sheng to expound the Book of Documents to her. Xiahou Sheng was then promoted to Privy Treasurer of Changxin Palace, and ennobled as Marquis Within the Passes.

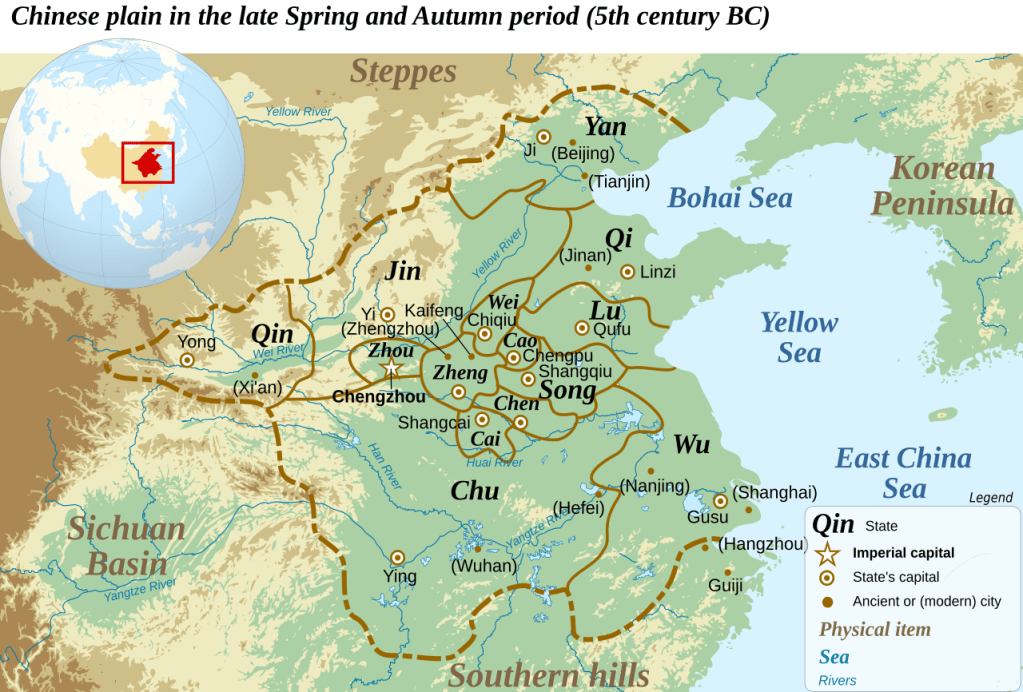

In former times, Crown Prince Liu Ju, born of Empress Wei, had taken to wife a Lady Shi of the kingdom of Lu, and she bore him a son, Liu Jin, styled the Emperor’s Grandson Shi. The Grandson Shi took to wife a Lady Wang of Zhuo Commandery, and she bore a son Liu Bingyi, who was styled the Imperial Great-Grandson. When the Great-Grandson was but a few months old, he was implicated in the witchcraft affair. The three sons and one daughter of the Crown Prince, with their wives and concubines, all perished in that calamity. Only the Great-Grandson survived, yet he too was cast into the commandery prison.

At that time, Bing Ji, former Associate Minister of Justice of Lu, was charged by decree to investigate the witchcraft case. Knowing the Crown Prince to be guiltless, he grieved for the unjust suffering of the Imperial Great-Grandson. He chose trustworthy and compassionate women among the inmates—Hu Zu of Weicheng and Guo Zhengqing of Huaiyang—to nourish the child, and placed him in a drier and cleaner cell. Bing Ji himself came every other day to inspect.

The witchcraft case dragged on unresolved. When Emperor Wu fell ill, he often lodged at the Changyang and Wuzha Palaces. Astrologers declared that an imperial aura arose within the prison at Chang’an. Emperor Wu therefore ordered that all prisoners there be executed, without regard to guilt or crime.

One night the palace usher Guo Rang came with men to the commandery prison, but Bing Ji refused to open the gates, saying: “Within is the Imperial Great-Grandson. To kill the innocent is unlawful; how much more the close kin of the Emperor!” He barred the gates until dawn. Guo Rang returned and impeached Bing Ji.

When Emperor Wu awoke and heard, he said: “This is Heaven’s intervention.” He issued a general amnesty, and only those imprisoned in the commandery residence were spared—preserved through the loyal protection of Bing Ji.

Later, Bing Ji, deeming it unfitting that the Imperial Great-Grandson should remain in prison, instructed the warden Shei Ru to present a letter to the Intendant of Jingzhao. Shei Ru, together with Hu Zu, carried the letter, but the Intendant refused to receive it and sent them back. When the time came for Hu Zu’s release, the Imperial Great-Grandson clung to her with longing. Bing Ji then spent his own wealth to persuade Hu Zu to remain, and with Guo Zhengqing she continued to rear the child. After some months, Hu Zu was permitted to depart.

Thereafter the county treasurer reported to Bing Ji that no decree authorized provisions for the Imperial Great-Grandson. Bing Ji again drew upon his own purse, each month supplying rice and meat. When the child fell ill, he arranged for wet-nurses without ceasing, and himself oversaw the use of medicines. Many times by such care Bing Ji drew the Imperial Great-Grandson back from the brink of death.

When Bing Ji learned that Consort Shi, grandmother of the Great-Grandson, had a mother Zhenjun and a brother Shi Gong, he sent the child in a carriage and entrusted him to them. The aged Zhenjun, beholding her sole great grandson, was moved with compassion, and took upon herself the burden of nurture, cherishing him with utmost care.

Later an imperial decree commanded that the Imperial Great-Grandson be raised within the inner palace, his name entered in the register of the Minister of the Imperial Clan. At that time Zhang He was Director of the Inner Palace. He had once served Crown Prince Liu Ju, and out of remembrance for former grace, pitied the orphaned scion. He tended the Imperial Great-Grandson with devotion, sustaining him and instructing him at his own expense. When the Great-Grandson reached maturity, Zhang He, seeking to strengthen his household bond, proposed to wed his granddaughter to him.

At that time Emperor Zhao had just come of age. His stature was eight feet two inches. Zhang He’s younger brother, Zhang Anshi, served as General of the Right and assisted in the government. When he heard that Zhang He praised the Imperial Great-Grandson and even thought to marry his granddaughter to him, he grew angry and said: “The Imperial Great-Grandson is but a remnant scion of Crown Prince Liu Ju and Empress Wei. It is fortunate enough that the state sustains him with the livelihood of a commoner. How can you speak of wedding him to our granddaughter?” Zhang He, hearing this, abandoned the plan.

At that time there was a clerk of the weaving chamber within the harem, eunuch Xu Guanghan. Zhang He gave a banquet and invited him. When the wine was deep, Zhang He said: “The Imperial Great-Grandson is a kin to the Emperor. At the least, he will bear the rank of Marquis Within the Passes. He would be a worthy match for your daughter.” Xu Guanghan agreed. On the morrow, when Xu’s wife heard of it, she was wroth; yet Zhang He pressed the matter, and in the end the marriage was made. Zhang He himself bore the expense of the dowry.

Thus the Imperial Great-Grandson relied upon the support of Xu Guanghan and his brethren, together with his grandmother’s house, the Shi clan. He received instruction in the Book of Songs from Fu Zhongweng of Donghai. Though he was quick of wit and ardent in study, he also delighted in knight-errant’s hobbies, such as cockfighting and dog-racing. In this he came to know the ways of good and evil among the people, and to discern the success and failure of local administration.

He roamed often through the counties and commanderies, visiting ancient tombs, and explored widely the Three Metropolitan regions of Jingzhao, Pingyi, and Fufeng. Once he met hardship near Lianshao Salt Lake, and he especially liked the counties of Du and Hu, and would often reside at Xiadu City. When entering court, he lodged in the quarter of Shangguanli outside the capital of Chang’an.