Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 15 Scroll 23

Duration of 12 years

The 1st year of Emperor Zhao’s Shiyuan Era (86 B.C.)

In summer, the tribes of twenty-four towns in Yizhou rose in rebellion, numbering more than thirty thousand. The Commandant of Waterways, Lü Bihu, summoned officials and civilians, and drew forth the troops of Qianwei and Shu commanderies to strike them. The rebels were routed, and a great victory was won.

In July of autumn, a general amnesty was proclaimed throughout the realm.

Heavy rains endured until October, the waters surged and swept away the bridge upon the Wei River.

When Emperor Wu first passed away, the new Emperor issued an edict of mourning to all the feudal lords. The Prince of Yan, Liu Dan, on receiving it, declined to wear mourning garb, saying, “The seal-envelope is smaller than before; surely some irregularity has arisen at the capital.” He dispatched his trusted men Shouxi Chang, Sun Zongzhi, Wang Ru, and others to Chang’an, outwardly to inquire into ritual observances, but in truth to spy upon court affairs.

The Son of Heaven, by decree, sent gracious words and bestowed gifts upon Liu Dan: three hundred thousand coins, with an increase of thirteen thousand households in his fief. Yet Liu Dan waxed wroth, saying, “It is I who should be enthroned as Emperor, not be given trifles.”

He conspired with his kin, the Prince of Zhongshan, Liu Chang, and Liu Ze, grandson of the Prince of Qi. Together they forged false decrees, alleging the late Emperor Wu having granted them governance and personnel of principalities, urging them to strengthen their armaments and make preparations beyond the ordinary.

The Gentleman of the Household, Cheng Zhen, admonished Liu Dan, saying, “Your Highness, why idly contend for what is yours by right? You must rise and seize it. When Your Highness raises the standard, even the women of the realm will rally to your cause.”

Thus Liu Dan entered into a secret covenant with Liu Ze, and together they composed a false proclamation to be spread abroad, declaring, “The young sovereign is no true son of Emperor Wu, but one foisted upon the throne by ministers. Let the whole realm rise together and strike him down!” Thereupon emissaries were dispatched to the provinces, sowing sedition among the people.

Liu Ze plotted to raise troops and march upon Linzi, intending to slay the Inspector of Qingzhou, Juan Buyi. Liu Dan gathered disloyal men from the provinces, amassed copper and iron to forge armor, conducted wapenshaws of his horsemen, chariots and infantry officers, and held great hunts to drill his soldiers, awaiting the appointed day.

The Palace Gentleman Han Yi and others often remonstrated with him, but Liu Dan grew wrathful, and slew fifteen men, Han Yi among them.

At that time, the Marquis of Ping, Liu Cheng, discerned Liu Ze’s treachery and secretly informed Juan Buyi. In August, Juan Buyi seized Liu Ze and his accomplices, and reported the matter to the throne.

The Son of Heaven dispatched the Associate Grand Herald to investigate, and summoned the Prince of Yan. By edict it was declared: “The Prince of Yan, being of close kin, shall be spared punishment.” Liu Ze and his followers were executed. Juan Buyi was promoted to Intendant of the Jingzhao(the Capital).

Juan Buyi, as Intendant of the Jingzhao, was held in reverence by both officials and the people. Whenever he went forth to circuit the counties or to review the prisons, his mother would inquire of him, saying, “Have you redressed any wrongs? How many have been acquitted?”

Whenever Juan Buyi overturned false judgments, his mother rejoiced greatly, her countenance more radiant than at other times. But if no injustices were set right, she grew wrathful and refused food. Thus Juan Buyi, in office, was stern yet not harsh, severe yet not cruel, ever weighing fairness in his judgments.

On September 2, Marquis Jing of Du, Jīn Mìdī, passed away. Earlier, when Emperor Wu lay ill, a testamentary decree had ordered that Jīn Mìdī be enfeoffed as Marquis of Du, Shangguan Jie as Marquis of Anyang, and Huo Guang as Marquis of Bolu, in recognition of their merits in subduing rebels such as Ma Heluo. Yet Jīn Mìdī, considering the tender age of the new Emperor, declined the title; Huo Guang and the others likewise did not dare to accept.

When Jīn Mìdī was stricken with grave illness, Huo Guang memorialized that he should be ennobled. As Jīn Mìdī lay upon his bed, the seal and ribbon were brought to him; he received them, but died that very day.

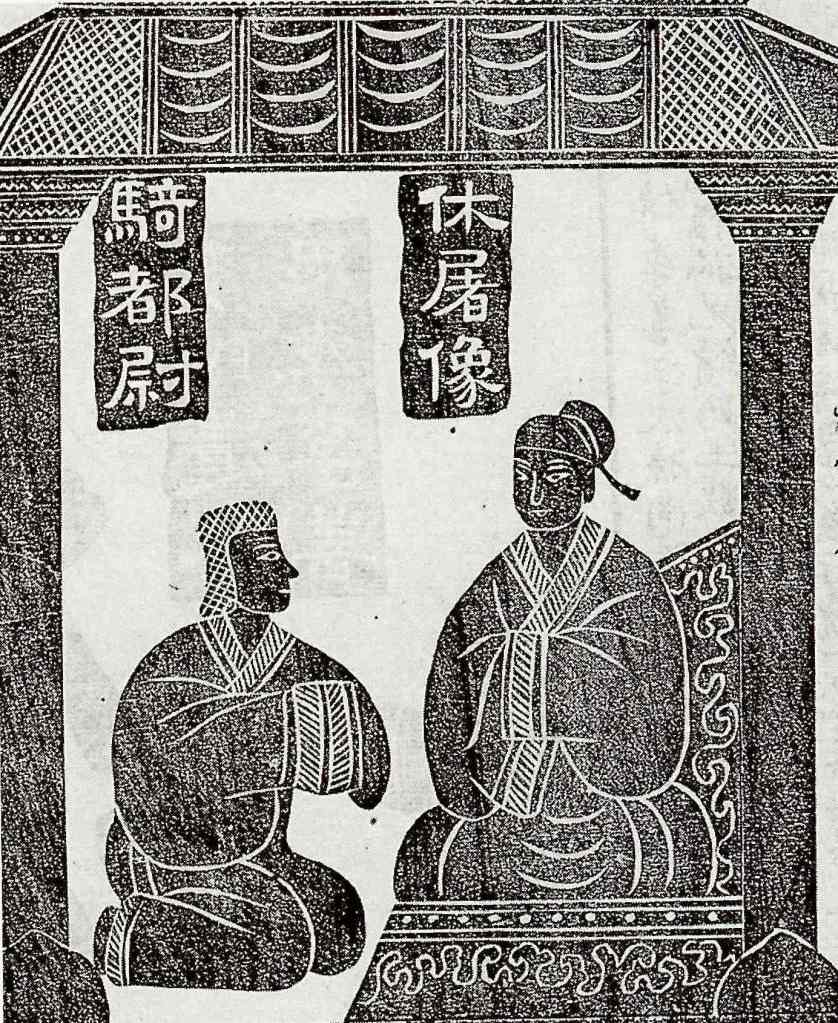

His two sons, Jin Shang and Jin Jian, both served as attendants to the new Emperor, being of near equal age. They slept and ate together. Jin Shang was appointed Commandant of the Imperial Chariot, and Jin Jian Commandant of the Imperial Cavalry.

After Jin Shang inherited his father’s marquisate, he bore two ribbons. The Emperor said to General Huo Guang, “The two brothers of the Jīn clan—should both of them wear two ribbons?”

Huo Guang replied, “Jin Shang inherited his father’s marquisate, thus he wears one ribbon more.”

The Emperor smiled, saying, “But is not the granting of titles a matter between you and me, General?”

Huo Guang answered, “It was the decree of the late Emperor, that titles be bestowed according to merit.” Thus the matter was put to rest.

In the intercalary month of October, the former Minister of Justice, Wang Ping, and others were dispatched, bearing the imperial sceptre, to make circuits through the provinces, to seek out men of virtue, to hear the grievances of the people, and to rectify cases of injustice and incompetence.

That winter was unseasonably warm, and no ice was formed.

The 2nd year of Emperor Zhao’s Shiyuan Era (85 B.C.)

In January of spring, General Huo Guang was enfeoffed as Marquis of Bolu, and General Shangguan Jie as Marquis of Anyang.

There were those who admonished Huo Guang, saying: “General, have you not observed the fate of the partisans of the Lü clan? Though they held the offices of Yi Yin and the Duke of Zhou, they grasped the reins of state alone, monopolized power, slighted the imperial clan, and shared not their duties with others. Thus the trust of the realm was lost, and ruin swiftly came upon them.

“Now you stand in a position of utmost weight, while the Emperor grows toward maturity. It is meet and right that you draw in the scions of the imperial house, confer with ministers, and reverse the ways of the Lü faction, so that calamity may be averted.”

Huo Guang assented to this counsel. He therefore summoned worthy men of the imperial clan, and appointed Liu Piqiang, grandson of Prince Yuan of Chu(Liu Jiao), and Liu Changle, of the imperial lineage, as Grand Master of Chamberlain. Liu Piqiang was further made Commandant of the Changle Palace Guard.

In March, envoys were dispatched to extend loans and relief to the poor who lacked seed grain and sustenance.

In August of autumn, an edict was issued, declaring: “In previous couple of years, calamities have been many. This year, the mulberry and wheat production suffers greatly. Let the loans and relief granted for seed and food not be repaid, and let the people be exempt from this year’s land tax.”

In earlier times, Emperor Wu had pursued the Xiongnu without respite for more than twenty years, whereby the Xiongnu suffered grievous losses in horses, livestock, and populace. The foaling of horses and calving of cattle declined sharply, and the Xiongnu were sorely troubled by the failing of their herds. Ever did they yearn for peace, yet no settlement was achieved.

The Chanyu Hulugu had a younger half-brother of the same father, who served as Left Grand Commandant, a man of talent and greatly esteemed among the people. But Hulugu’s mother, Zhuanqu Yanzhi, feared her son would be set aside and the younger brother chosen as heir. She therefore caused him to be secretly slain.

An elder brother of the Left Grand Commandant, born of the same mother, nourished hatred in his heart and refused to attend the Chanyu’s court.

In that year, the Chanyu fell gravely ill and neared death. He spoke to the nobles, saying: “My sons are yet young and cannot rule the state. I would appoint my brother, the Right Guli King, to succeed me as Chanyu.”

When the Chanyu died, Wei Lü and others conspired with Zhuanqu Yanzhi to conceal the news. They forged a decree in the Chanyu’s name, and set up her son, the Left Guli King, as the new Chanyu, taking the title Huyandi.

The Left Tuqi King and the Right Guli King bore anger and resentment. With their followers, they resolved to march south and surrender to the Han. Fearing they could not accomplish this alone, they compelled King Lutu to defect with them to the Western Wusun.

King Lutu revealed their plot to the Chanyu. The Chanyu sent envoys to question them, but the Left Guli King refused obedience, and in turn accused King Lutu of treason. The people bewailed the injustice.

Thereafter, the two princes departed, each establishing his own dwelling, and no longer appeared at the Chanyu’s court–Longcheng, where deities were worshiped. From this time, the power of the Xiongnu waned.