Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 12 Scroll 20

Duration of 9 years

The 5th year of Emperor Wu’s Yuanshou Era (118 B.C.)

On March 11 of spring, Chancellor Li Cai was accused of appropriating empty land from Emperor Jing‘s Garden for the burial of his family. He was subsequently put on trial and, unable to endure the shame, committed suicide.

The three-zhu coins were discontinued, and five-zhu coins were minted in their place. This change led to a rise in counterfeiting, especially in the Chu region.

The Emperor appointed Ji An as the new Prefect of Huaiyang, located on the outskirts of the Chu region. Despite Ji An‘s humble refusal to accept the seal of authority, the decree was repeatedly insisted upon until Ji An reluctantly acquiesced. With tears in his eyes, Ji An spoke to the Emperor: “I have always thought of myself as being cast aside in ditches and valleys, never expecting to be employed by Your Majesty again. I often suffer from ailments, like dogs and horses, that rendered me incapable of handling the duties of a commandery. I am only fit to serve as a Palace Attendant, assisting in the rectification of mistakes and oversights within the imperial court.”

The Emperor responded, “Do you disdain the position of Prefect of Huaiyang? I will call you back soon enough, but the officials and people of Huaiyang are not in their rightful places. I rely solely on your renown and stature. You will surely manage it, even from your bed.”

After Ji An bid farewell and departed, he encountered Li Xi, the Grand Usher, and said, “By being exiled and accepting the commandery post, I have lost the opportunity to engage in state affairs with the court. The Grand Master of the Censorate, Zhang Tang, is shrewd enough to counter objections, deceptive enough to conceal faults, and skilled in the art of flattery and rhetoric. However, he refuses to speak truthfully for the good of the world, instead catering solely to the Emperor’s desires. If the Emperor dislikes something, Zhang Tang disparages it; if the Emperor likes something, Zhang Tang praises it. He eagerly engages in petty matters, using convoluted arguments to sway the Emperor’s thoughts, and employs corrupt officials to strengthen his own authority. You, being one of the Nine Ministers with access to the Emperor, must speak out early; otherwise, you will fall with him and be destroyed.”

Li Xi, fearing Zhang Tang, dared not oppose him. Later, when Zhang Tang was prosecuted, the Emperor accused Li Xi of complicity.

Ji An was assigned to govern Huaiyang with the salary of a minister of a feudal lord (2000 picul), where he remained for ten years until his death.

An edict was issued to relocate corrupt officials and lawbreakers to the border regions.

In the summer, On April 2, the Grand Tutor to the Crown Prince, Marquis Wuqiang, Zhuang Qingzhai, was appointed as Chancellor.

The Emperor fell gravely ill at Dinghu Palace. Despite the efforts of sorcerers and physicians, there was no improvement. Youshui Fagen mentioned a shaman in Shangjun Commandery who could communicate with spirits and cure illnesses. The Emperor summoned the shaman and allowed him to preside over sacrifices at Ganquan Palace.

As the illness worsened, an emissary was sent to consult the demigod(i.e. the shaman) for advice. The demigod responded, “The Emperor’s illness is not a cause for concern; it will soon subside. You should come to meet me at Ganquan despite how you feel.” Soon after, the Emperor’s condition improved, and he visited Ganquan Palace, recovering quickly.

Once the illness had fully subsided, a banquet was arranged at the Shou Hall, where the demigod resided. Though the demigod could not be directly seen, his words were heard by others and sounded human. He appeared and then disappeared, accompanied by a solemn wind, and resided within curtained chambers. His words, which the Emperor received, were recorded as “The Plan.” While his advice contained nothing extraordinary and was rooted in common knowledge, the Emperor took great pleasure in it. The details were kept secret, and no one outside the palace knew of them.

While traveling to Ganquan Palace, the Emperor passed through the Right Interior Minister’s jurisdiction and discovered many paths were neglected and poorly maintained. Enraged, the Emperor exclaimed, “Does Yi Zong think I would never use this road again?” He bit his own lip in anger.

The 6th year of Emperor Wu’s Yuanshou Era (117 B.C.)

In October of winter, it rained, though there was no ice.

The previous year, the Emperor issued the min coinage edict, urging people to declare their assets and donate in the manner of Bu Shi. However, the people refused to contribute their wealth to support the county officials. As a result, Yang Ke dispatched agents to report on those who hid their assets and violated the min coinage laws. Yi Zong, seeing the agents’ actions as disruptive to the people’s lives, arrested them. The Emperor considered this an act of defying imperial orders and interfering with law enforcement, leading to Yi Zong‘s public execution.

Chamberlain Li Gan, harboring resentment for the death of his father, Li Guang, at the hands of the Grand General Wei Qing, attacked and wounded Wei Qing. The General concealed the incident. Shortly thereafter, Li Gan accompanied the Emperor to Yong and arrived at the hunting grounds of Ganquan Palace. There, General of the Agile Cavalry, Huo Qubing, shot and killed Li Gan. At that time, Huo Qubing enjoyed great favor and held a high rank, so the Emperor covered up the killing, claiming that Li Gan was killed by a rampaging deer.

On April 28 of the summer, in a ceremony at the Grand temple, Prince Liu Hong was named the Prince of Qi, Liu Dan as the Prince of Yan, and Liu Xu as the Prince of Guangling. This marked the precedence of the initial enunciation of the prince titles by imperial written certificates.

Since the minting of silver and five-zhu coins, tens of thousands of officials and civilians who were caught counterfeiting coins had been executed. The number of undetected cases was countless, and practically throughout the entire country, there was no one who had not been somehow involved in the casting of metal coins. The offenders were numerous, and the officials could not execute them all.

In June, an edict was issued to send six erudites, including Chu Da and Xu Yan, to thoroughly investigate the states and commanderies. They were tasked with identifying those engaged in illegal annexation of private properties or farm land, as well as officials, governors, and others guilty of crimes.

In September of the autumn, the Marquis of Guanjun [Champion] and Marquis of Jinghuan, Huo Qubing, passed away. The Emperor mourned his death deeply and had a tomb constructed in his honor, shaped like Qilian Mountain.

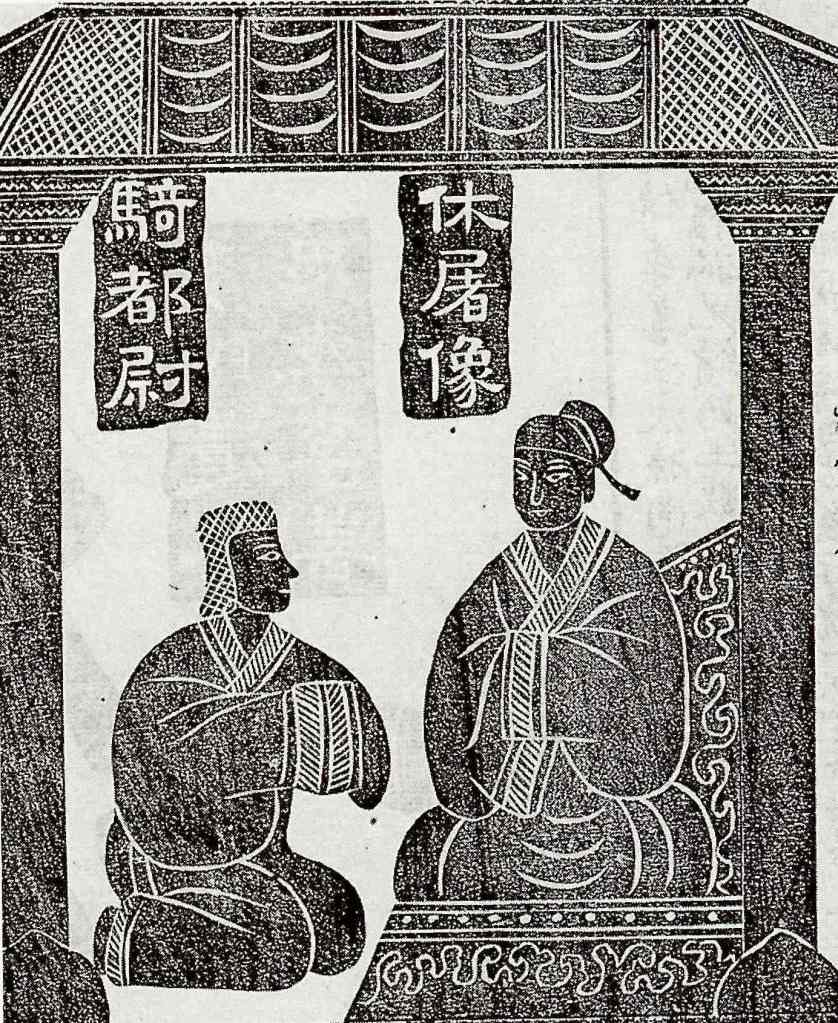

Huo Qubing’s father, Huo Zhongru, had completed his government service and returned home. There, he married and had a son named Huo Guang. As Huo Qubing grew older, he learned that Huo Zhongru was his father. While serving as the General of Agile Cavalry and battling against the Xiongnu, he passed through Hedong. He sent officials to invite Huo Zhongru to meet him and bought land, houses, slaves, and maidservants before departing. Upon his return, Huo Qubing brought Huo Guang with him to Chang’an, appointing him as an attendant-gentleman. Huo Guang was gradually promoted to the rank of Colonel of Royal Carriages and Grandee of Chamberlain.

During this year, the Minister of Agriculture, Yan Yi, was executed.

Yan Yi was renowned for his integrity and gradually rose to the position of one of the Nine Ministers. When the Emperor inquired about the creation of the white deerskin coins with Zhang Tang, Yan Yi expressed his opinion, saying, “Now, when princes and marquises offer tribute in the form of black jade discs, worth only a few thousand, the jade discs are wrapped in deerskins valued at hundreds of thousands. That is like putting the cart before the horse.” The Emperor was displeased with this response.

Later, Zhang Tang had a personal conflict with Yan Yi. When someone accused Yan Yi of another offense, the Emperor ordered Zhang Tang to decide on his punishment. On one occasion, Yan Yi‘s retainer remarked that an edict had certain improprieties, and Yan Yi responded with a slight movement of his lips, without speaking a word. Zhang Tang reported this, “Yan Yi, one of the Nine Ministers, noticed an inappropriate decree but failed to speak out about it, instead silently expressing his negative view. He is to be sentenced to death.” This incident established a criminal precedent in the law regarding “silent badmouthing” (Silence Disaccord), leading three excellencies and ministers to flatter and seek favor by speaking in a subservient manner.