Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 18 Scroll 26 (continued)

The 1st year of Emperor Xuan’s Shen’jue Era (61 B.C. continued)

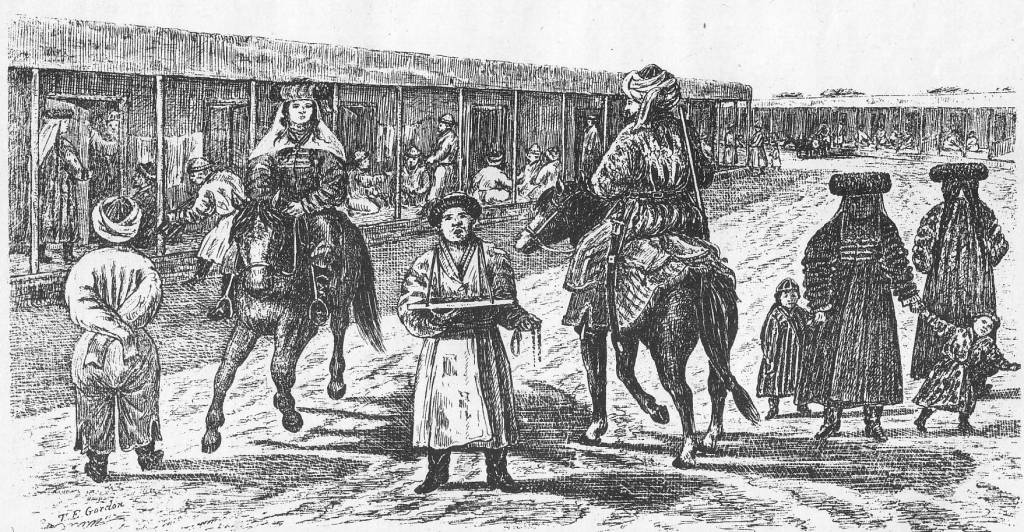

The Grandee of Merit, Yiqu Anguo, advanced into Qiangzhong. More than thirty influential Xianling leaders were summoned, and those deemed especially cunning and treacherous were executed. Troops were then released to strike the Xianling tribes, taking over a thousand heads. As a result, the surrendered Qiang and those who had submitted to the Han—such as the Qiang Marquis of Guiyi, Yang Yu—grew resentful and distrustful. They began raiding small settlements, rebelling against the frontier, assaulting towns and cities, and killing local officials. Yiqu Anguo, serving as Cavalry Commandant with three thousand horsemen under his command, was ordered to guard against the Qiang. But upon reaching Gaomen, he fell into an ambush, losing many chariots and weapons. He withdrew to Lingju county and reported the matter to the court.

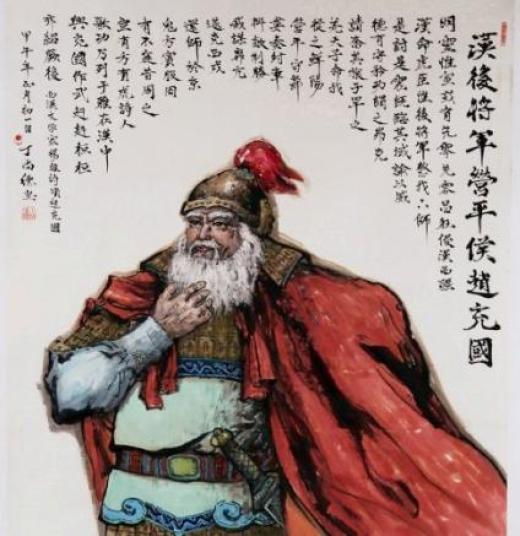

At that time, Zhao Chongguo was over seventy years of age. Believing him perhaps too old, the Emperor sent Bing Ji to inquire whom he thought capable of leading the army. Zhao Chongguo replied, “There is no one more seasoned for this task than this old officer.”

The Emperor summoned him and asked, “General, how do you judge the Qiang barbarians? How many troops are required?”

Zhao Chongguo responded, “To hear a hundred second-hand tales is not equal to seeing once with your own eyes. It is difficult to grasp the situation from afar. I request permission to hurry to Jincheng and devise the strategy in person. The Qiang and Rong, and the lesser tribes among them, are rebellious and shifting—surely near collapse. I ask Your Majesty to entrust this old servant and harbor no doubt.”

The Emperor laughed, saying, “So be it.” He then mobilized a great army to advance on Jincheng commandery.

In April of summer, Zhao Chongguo was appointed to command the campaign against the Western Qiang.

In June, a comet appeared in the eastern sky.

When Zhao Chongguo reached Jincheng, he planned to cross the Yellow River only after ten thousand cavalry had assembled. However, fearing interception by the enemy, he dispatched three detachments bearing torches to cross first under cover of night, ordering them to establish fortifications immediately upon landing. By dawn the crossing was complete, and several dozen to a few hundred enemy horsemen appeared, circling around the army.

Zhao Chongguo said, “Our men and horses are weary from the journey—we must not pursue lightly. These riders are elite, and difficult to command against. Moreover, this is likely a stratagem to lure us into battle. Our purpose is to crush the enemy; trifling victories are not worth the risk.” He then forbade his troops to give chase.

He sent equestrian scouts ahead toward Siwang Gulch. When they reported no enemy presence, he led the army through the gulch by night and proceeded to Mount Luodu. Summoning his lieutenants, Zhao Chongguo said, “I am certain the Qiang cannot inflict real harm. Had they stationed even a few thousand to guard Siwang Gulch and bar our passage, how could we have come through so easily?”

Zhao Chongguo regularly sent scouts far ahead to reconnoiter, prepared for battle even while marching, and fortified his camps whenever he halted. He was cautious in all things, valued the lives of his soldiers, and calculated before committing to combat. From Mount Luodu he advanced westward to the headquarters of the Western Commandant, where he held feasts daily for his troops, whose morale surged and who all longed for action. Though the enemy repeatedly provoked him, Zhao Chongguo remained resolute and would not engage.

After several prisoners were captured alive, they confessed that the Qiang chieftains chastised one another, saying: “I told you we should not rebel! Now the Emperor has sent General Zhao—eighty or ninety years of age, yet unmatched in the art of war. Even if we wished to fight to the death, would we even have the chance?”

Earlier, the chieftain of the Han and Jian tribes, Midanger, had sent his younger brother Diaoku to report to the Commandant that the Xianling tribe were preparing to rebel. Several days later, they indeed rose in revolt. Since many of Diaoku’s kinsmen were aligned with the Xianling, the Commandant held him as a hostage. Zhao Chongguo, judging him blameless, released him and sent him back with a message for the Xianling chieftains, declaring: “The imperial army punishes only the guilty, sparing the innocent. The Emperor proclaims to all Qiang people: whoever captures lawbreakers shall be rewarded in proportion to the gravity of their captives’ crimes, with gold bestowed accordingly, and the wives, children, and property of the captured awarded as well.” Zhao Chongguo’s design was to employ imperial authority to win over the Han and Jian tribes and those among the raiders who might submit, thereby unsettling the enemy’s plans, exploiting their fatigue, and then striking once their strength faltered.

At this time the Emperor had already dispatched sixty thousand troops from the inner commanderies to strengthen the border garrisons. The Prefect of Jiuquan, Xin Wuxian, submitted a memorial stating:

“The commandery garrisons all sit defensively in the southern mountains, leaving the northern frontier exposed—this cannot sustain. If we wait until autumn or winter to advance, such a plan suits only when the enemy is far away. Now they raid us day and night, and the land is bitterly cold. Han horses cannot endure the winter. It would be better to provision our troops in early July with thirty days’ supplies, divide them into two columns, and attack from Zhangye and Jiuquan, converging upon Han and Jian tribes along the Xianshui River. Even if we cannot exterminate them entirely, we may seize their livestock, take their wives and children, and then withdraw. In winter we may strike again, and when the main force advances thereafter, the enemy will surely be thrown into turmoil.”

The Emperor forwarded Xin Wuxian’s letter to Zhao Chongguo for feedback. Zhao Chongguo replied:

“Each horse can carry no more than thirty days of grain—two and a half bushels of rice or eight bushels of wheat—besides clothing and arms. Pursuit would be difficult. The enemy will doubtlessly rely on shifting maneuvers, withdrawing gradually, following water and pasture, scattering into mountains and forests. If we chase deeply, they will seize the heights and sever our supply lines, placing us in extreme peril. We would become a joke to the barbarians, and the humiliation would not be washed away for a thousand years. As for Xin Wuxian’s proposal that we seize their livestock and capture their wives and children, this is more hope than strategy, not something that can be relied upon. The Xianling tribe rose first in rebellion, and the other tribes only followed them in raiding and kidnapping. Therefore, this old officer proposes that we acknowledge the excesses committed by the Han and Jian tribes, conceal their offenses, and refrain from exposing them. We should first suppress the Xianling to inspire fear, after which they will seek to correct themselves. Then we may pardon their crimes, appoint capable officials familiar with their customs, and gently guide them toward reconciliation. This is the only plan that protects the whole army and truly secures the frontier.”