Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 7 Scroll 15 (continued)

The 7th year of the Emperor Wen’s Later Era (157 B.C.)

In the summer, on June 1, the Emperor passed away in the Weiyang Palace. In his posthumous edict, he stated:

“We have heard that all things in the world are destined to perish. Death is part of the natural order of Heaven and Earth, so why should we be overly sorrowful? In the present age, people cherish life but fear death. They spend extravagantly on funerals, burdening their families with financial difficulties. They mourn excessively, causing harm to their own well-being. We are firmly against this practice. As for myself, we have not been virtuous enough to truly serve the people. Now, in my passing, we do not wish to burden them further by imposing long periods of mourning, subjecting them to the hardships of cold and heat, causing sorrow to fathers and sons, and hurting the feelings of the elderly. It would also disrupt their food and drink consumption and interrupt the sacrifices to gods and spirits. How can we, with my lack of virtue, do such things to the people of the realm?

“We have been fortunate to safeguard the ancestral temple and, with my feeble and short stature, ruled over the kings of the realm for over twenty years. Through the blessings of Heaven and the ancestors, there has been peace within the borders, and no wars or upheavals. Though we are witless, we have always been mindful of not tarnishing the virtues left by my predecessor through my mistakes. Over a long period, we constantly worried about not being able to fulfill my duties until the end. Now, by the grace of my allotted years, we are able to once again join Emperor Gaozu in the ancestral temple. What is there to mourn for? We hereby decree that upon the arrival of this order, after three days, all mourning garments should be removed. There should be no restrictions on marriage, funeral rites, drinking alcohol, or consuming meat. Those who need to be present for mourning rituals should not go barefoot. The width of mourning belts should not exceed three inches. No carriages or weapons should be displayed. Do not mobilize people to wail in the palace halls. Those who are to be present in the halls should wail 15 times at dawn and dusk, and after the completion of the rituals, they must stop mourning. Outside the windows of wailing time at dawn and dusk, people are forbidden to mourn in the palace halls without permission.”

“After the coffin is lowered, those wearing the Large Gong (mourning garment for close relations) should wear it for fifteen days, those wearing the Little Gong (mourning garment for slightly distant relations) for fourteen days, and those wearing Sima (hemp mourning garment for distant or maternal relations) for seven days. After that, mourning garments should be removed. Any other matters not mentioned in this decree should follow its intent. Announce this decree to the entire realm so that they may understand my intentions. Let the hills and rivers around the Ba mausoleum remain unchanged. The female officials, from Consort Madame down to minor envoy (the lowest rank of palace lady), should return to their homes.”

On June 7, the burial took place at the Ba mausoleum.

During the Emperor’s reign of twenty-three years, he made no additions to the palaces, imperial gardens, carriages, honor guards, or formal attire. Whenever there was an inconvenience to the public, he swiftly dropped the project for the benefit of the people. Once, he desired to build a terrace and summoned craftsmen to estimate the cost, which amounted to a hundred gold coins. The Emperor said, “A hundred gold coins represent the wealth of ten average households. We have inherited the palaces of my predecessor and always feared bringing shame upon them. How can we justify the construction of a new terrace?” He personally wore black silk garments. His beloved Consort, Madame Shen, also wore clothes that did not trail on the ground. The curtains and canopies had no ornate embroidery, demonstrating simplicity and setting an example for the entire realm.

In the construction of the imperial Ba mausoleum, only earthenware was used, without any decorations of precious metals such as gold, silver, copper, or tin. The tomb followed the natural contours of the mountain without constructing a mound. When the Prince of Wu feigned illness and did not attend court, the Emperor sent him canes and tables as a gesture of concern. Despite abrasive remonstrations from ministers like Yuan Ang and others, their advice was often accepted and implemented. General Zhang Wu and others received bribes in the form of gold and silver, but when discovered, they were given additional rewards to shame their corrupt behavior and stir guilt in their hearts. The Emperor was dedicated to governing with virtue and educating the people. As a result, there was peace and tranquility throughout the realm, and the people’s needs were fulfilled. Few rulers in later generations could compare to his achievements.

On June 9, the Crown Prince ascended the throne, and Empress Dowager Bo was honored as Grand Empress Dowager, while the empress was honored as Empress Dowager.

A comet appeared in the western sky in September.

This year, the King of Changsha, Wu Zhu, passed away without leaving an heir, and the kingdom was abolished.

Initially, Emperor Gaozu honored the King Wen of Changsha, Wu Rui, and issued an edict stating, “The loyal King of Changsha shall keep his title as a king.” However, during the reigns of Emperor Hui and Empress Dowager Lü, the descendants of King Wu Rui were enfeoffed as marquises, but the lineage was discontinued after several generations.

The 1st year of the Emperor Jing’s Early Era(156 B.C.)

In October, during the winter, Chancellor Shentu Jia and others submitted a memorial stating: “No one has achieved greater merit than Emperor Gaozu, and no one has exhibited greater virtue than Emperor Wen. The temple title of Emperor Gaozu should be called Taizu of Han, and the temple title of Emperor Wen should be called Taizong of Han. Sovereigns of later generations should continue to pay homage to these ancestral temples from generation to generation, and the various commanderies and principalities should each establish temples for Emperor Wen as Temple of Taizong.” The imperial response was, “It is appropriate.”

On April 22, a general amnesty was granted throughout the empire.

Grand Master of the Censorate, Tao Qing, was dispatched to the border of Dai Commandery to negotiate peace and a marriage alliance with the Xiongnu.

In May, the policy of collecting half of previous taxes on cultivated land was reinstated, with a tax rate of one-thirtieth. (Emperor Wen had initially reduced the taxes to half, and later to nothing.)

Emperor Wen abolished mutilation punishments, but the so-called “lighter” punishments often resulted in death. Those sentenced to have the toes of their right foot cut off still faced death, and those to lose the toes of their left foot were subjected to five hundred strokes of flogging, with many dying as a result. Those sentenced to have their noses cut off received three hundred strokes, with similar fatal outcomes. That year, an edict was issued: “The severity of flogging is no different from punishments for serious crimes. Even if one is fortunate enough to survive, they cannot live healthily afterward. The new laws are as follows: five hundred strokes will be reduced to three hundred, and three hundred strokes will be reduced to two hundred.”

Additionally, Zhou Ren, an advisor to the emperor, was appointed Grand Chamberlain; Zhang Ou became Minister of Justice; Marquis of Pinglu Liu Li, son of Prince Yuan of Chu, became Minister of Imperial Clans; and Chao Cuo, Grandee of the Palace, was made Interior Minister of the Left.

Zhou Ren, the palace guard captain for the Crown Prince, gained favor through his honesty and integrity. Zhang Ou, who also served the Emperor at the Crown Prince’s palace, was knowledgeable in legal matters but displayed great magnanimity. The Emperor valued them highly and promoted them among the Nine Ministers. Zhang Ou never used his position to persecute others, instead focusing on appointing honest and respectable individuals. His subordinates treated him with respect and dared not deceive him.

The 2nd year of the Emperor Jing’s Early Era (155 B.C.)

In December, during the winter, a comet appeared in the southwest.

A decree was issued lowering the age for mandatory civic duty from twenty-three to twenty for all males in the empire.

In the spring, on March 27, the imperial sons were granted princely titles: Liu De was made Prince of Hejian, Liu Yan became Prince of Linjiang, Liu Yu was appointed Prince of Huaiyang, Liu Fei became Prince of Runan, Liu Pengzu was made Prince of Guangchuan, and Liu Fa was appointed Prince of Changsha.

In the summer, on April 25, the Grand Empress Dowager, Lady Bo, passed away.

In June, Chancellor Shentu Jia also passed away. At that time, the interior minister Chao Cuo, frequently offered private advice and suggestions to the Emperor, many of which were accepted. This earned him favor and influence, allowing him to surpass the other nine ministers. He implemented several changes to laws and regulations, which displeased Chancellor Shentu Jia. Chancellor Shentu Jia took exception to Chao Cuo‘s rise and disliked him.

As interior minister, Chao Cuo found it inconvenient to use the eastern gate, so he had a new one constructed in the south. This new gate was near the temple of the Emperor Emeritus. When Chancellor Shentu Jia heard that Chao Cuo had pierced the wall of the Emperor Emeritus’s temple, he submitted a memorial requesting Chao Cuo’s execution. Rumors circulated that Chao Cuo became fearful, prompting him to secretly visit the palace at night to pay his respects and explain himself to the Emperor.

The following morning, during the court session, Chancellor Shentu Jia again requested Chao Cuo‘s execution. However, the Emperor responded, “The wall Chao Cuo penetrated is not the actual temple wall but an outer wall where unnecessary officials reside. Moreover, I ordered the work, so Chao Cuo is not guilty.” Chancellor Shentu Jia apologized and withdrew his request. After the session, Shentu Jia told his chief-of-staff, “I regret not having executed Chao Cuo before presenting my case to the Emperor. I have been deceived by him.” Upon returning home, Chancellor Shentu Jia vomited blood and died. Chao Cuo’s status and influence only grew stronger as a result.

In autumn, a peace treaty and marriage alliance were established with the Xiongnu.

On July 21, Tao Qing, the Marquis of Kaifeng and Grand Master of the Censorate, was appointed Chancellor. On August 2, Chao Cuo, the Interior Minister, was appointed Grand Master of the Censorate.

A comet appeared in the northeast.

During autumn, heavy rain and hail struck Hengshan, with some hailstones as large as five inches, and rainwater accumulating to a depth of two feet. Mars retrograded and stayed close to the North Star, while the moon passed through the North Star in an unusual manner. Saturn also retrograded and remained within the Supreme Palace Enclosure constellation.

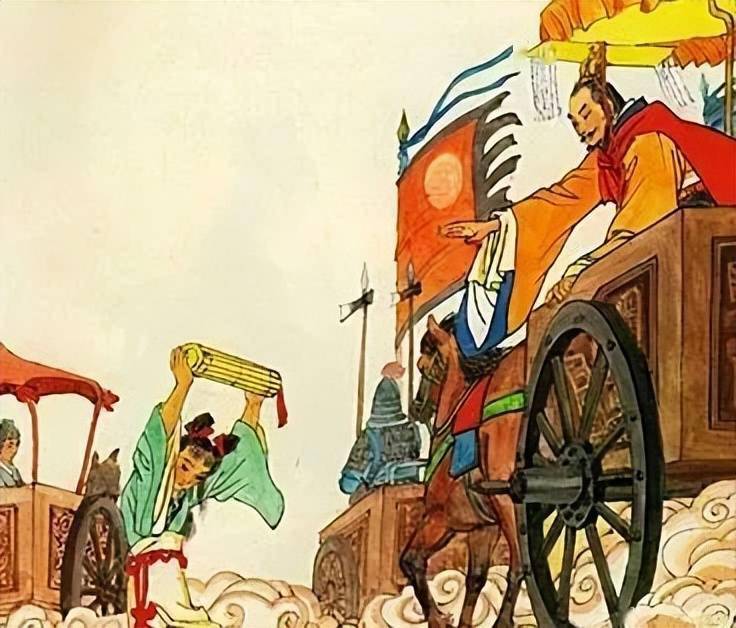

Prince Xiao of Liang, the youngest son of Empress Dowager Dou and her favorite, controlled over forty cities and governed the most fertile lands in the country. He received endless rewards and gifts, with his treasury holding millions in gold coins and even more precious gems and treasures than the capital. He constructed the Eastern Park, which spanned over three hundred li, and expanded the city of Suiyang by seventy li. Grand palaces and covered walkways were built, connecting platforms over a distance of more than thirty miles. He gathered talented individuals from across the land, including Mei Sheng, Yan Ji from Wu, Yang Sheng, Gongsun Gui, and Zou Yang from Qi, and Sima Xiangru and others from Chu, who enjoyed his patronage and accompanied him in his leisurely pursuits.Whenever Prince Xiao of Liang came to court, the Emperor sent special envoys with insignia and imperial wagons to welcome him at the pass. Upon his arrival, his influence was unmatched. He rode with the Emperor in the same carriage during court sessions, and they would hunt and engage in archery together in the Imperial Forest. Prince Xiao frequently submitted memorials requesting to stay in the capital for an additional six months. The attendants, attendants-in-waiting, and internuncios of Liang were registered and allowed to enter and exit the imperial palace, resembling the eunuchs of the Han court.