Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 8 Scroll 16 (continued)

The 3rd year of the Emperor Jing’s Early Era (154 B.C. continued)

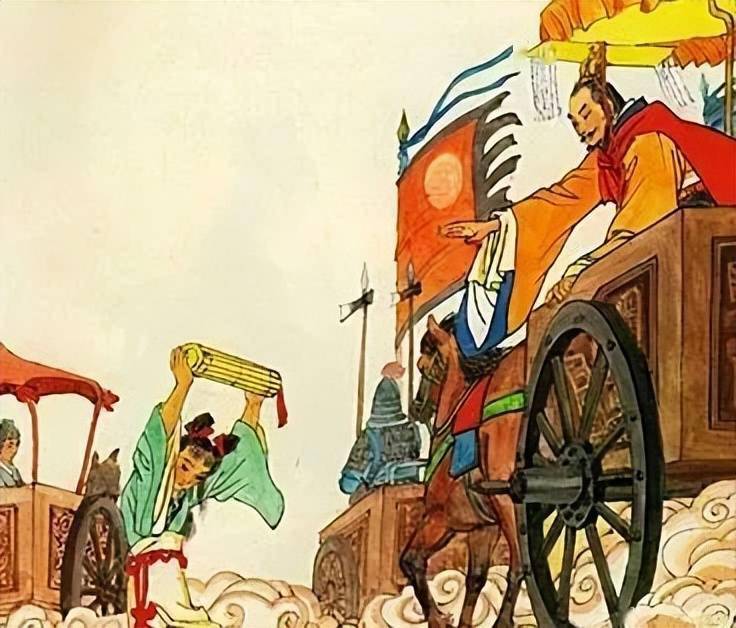

The Grand Commandant, Zhou Yafu, addressed the Emperor: “The Chu soldiers are agile, fierce and difficult to confront head-on. I propose abandoning the defense of Liang and instead cutting off the enemy’s supply routes—only then can we gain the upper hand of the situation.” The Emperor approved his strategy. Zhou Yafu, riding in a six-horse carriage, led his troops to assemble at Xingyang.

Upon reaching Bashang, a commoner named Zhao She stopped his carriage and offered counsel: “The Prince of Wu, known for his wealth, has long gathered loyal and brave soldiers. It is highly likely he has set ambushes along the narrow passages of Mount Xiao and Lake Mianchi. Military strategy values the element of surprise—why not take an alternative route? Travel through Lantian, exit via Wu Pass, and reach Luoyang. The detour will cost only an extra day or two, but you will arrive directly at the armory and sound the war drums. When the other princes hear of it, they will think you have descended from Heaven.”

Zhou Yafu followed this idea and reached Luoyang. Pleased, he remarked: “The seven princedoms have rebelled, yet I have traveled this far by fast carriage and arrived safely. Now that I am stationed in Xingyang, there is no cause for concern east of here.” He ordered a search of the area between Mount Xiao and Lake Mianchi, where the Prince of Wu’s hidden troops were indeed discovered. He then appointed Zhao She as Protector of Army.

Zhou Yafu withdrew his forces northeast toward Changyi. Meanwhile, Prince of Wu’s troops continued their siege of Liang, and the Prince of Liang repeatedly sent messengers pleading for reinforcements. Zhou Yafu, however, refused to dispatch aid. The Prince of Liang then appealed directly to the Emperor, who commanded Zhou Yafu to relieve the urgency of Liang. Yet Zhou Yafu defied the imperial order, choosing instead to remain fortified and avoid direct confrontation. He dispatched the Marquis of Gonggao, Han Tuidang, along with a light cavalry unit to the Huai-Si River crossing, severing the retreat routes and supply lines of Wu and Chu.

The Prince of Liang appointed Grandee of the Palace Han Anguo and Zhang Yu, the younger brother of Prime Minister of Chu, Zhang Shang, as commanders of the army. Zhang Yu was fierce in combat, while Han Anguo was cautious and held his position. Together, they inflicted significant damage on the forces of Wu.

The troops of Wu attempted to retreat westward, but the Prince of Liang’s strong defenses blocked their path. Turning instead toward Marquis of Tiao’s camp, they prepared for battle. However, Zhou Yafu steadfastly maintained his defensive position and refused to engage. The forces of Wu, facing severe food shortages, repeatedly issued challenges, but Zhou Yafu remained inside the camp.

One night, a riot broke out inside Marquis of Tiao’s camp—soldiers, confused and agitated, began fighting among themselves, and the chaos spread dangerously close to Zhou Yafu’s tent. Yet he remained resolute, refusing to rise. Soon, order was restored.

As desperation grew, the forces of Wu appeared to concentrate on the southeast, while Zhou Yafu repositioned his troops to the northwest. Later, Wu’s elite soldiers attempted a breakthrough in the northwest but were blocked and forced to withdraw.

Many soldiers of Wu and Chu perished from starvation or deserted due to the lack of provisions. Unable to sustain their campaign, the rebel forces ultimately withdrew.

In February, General Zhou Yafu led his elite troops in pursuit, delivering a decisive defeat to the retreating enemy. Prince of Wu, Liu Pi, abandoned his army and fled under the cover of night with only a few thousand warriors. Prince of Chu, Liú Wù, seeing no escape, took his own life.

When the Prince of Wu launched his campaign, he appointed his minister, Tian Lubo, as Grand General. Tian Lubo proposed a plan: “If we concentrate our forces and march westward, we will have no alternative routes to take, making success difficult. I suggest leading fifty thousand troops along the Yangtze and Huai rivers to seize Huainan and Changsha, then enter Wu Pass to join the main army. This unexpected maneuver would catch the enemy off guard.”

However, the Crown Prince of Wu, Liu Ju, dissuaded him: “Since we march under the banner of insurrection, entrusting another with command poses a grave risk—what if they turn against Sire? Moreover, dividing our forces invites danger, yielding only disadvantages and harm.” The Prince of Wu heeded his warning and rejected Tian Lubo’s plan.

Earlier, a young officer, General Huan, had advised the Prince: “Wu’s strength lies in its infantry, which excels in rough terrain, while Han relies on cavalry and chariots, which dominate open ground. I propose that instead of besieging cities, we advance swiftly, seizing Luoyang’s weapon warehouses and the grain stores at Ao’cang. With mountains and rivers as natural defenses, we can rally other monarchs. Even without entering Hangu Pass, we will secure control of the realm. But if Sire moves too slowly, preoccupied with capturing cities, once Han’s cavalry and chariots thrust into the outskirts of Liang and Chu—then we will face disaster.”

The Prince of Wu consulted his veteran generals, but they dismissed Huan’s strategy: “He is young—suited for charging into battle, not for devising grand strategy.” Thus, the Prince did not adopt his plan.

When the Prince of Wu assumed sole command of the military, just before crossing the Huai River, he appointed all his retainers and attendants as generals, colonels, sentinels, and majors—except for Zhou Qiu. A native of Xiapi, Zhou Qiu had once been a fugitive in Wu, known for his addiction to alcohol and reckless behavior. The Prince distrusted him and assigned him no responsibilities.

Feeling slighted, Zhou Qiu sought an audience with the Prince and said, “I am aware of my shortcomings, yet I have been given no opportunity to prove myself. I do not dare ask for a position, but if Sire grants me a tally, I swear to repay it with results.” The Prince agreed and handed him a tally.

That night, Zhou Qiu hastened back to Xia’pi. By then, news of Wu’s rebellion had already reached the city, and the local authorities were on high alert. Upon arrival, he lodged at an inn and summoned the Prefect of Xia’pi under false pretenses. Once the prefect entered his room, Zhou Qiu’s attendants executed him on fabricated charges.

Afterward, he gathered influential local leaders, many of whom were acquaintances of his brother, and declared, “Wu has risen in rebellion, and its forces will arrive before midday. If we surrender now, our families will be spared, and those who prove their worth will be rewarded with noble titles.” The words quickly spread, and by morning, the entire city of Xia’pi had surrendered.

In a single night, Zhou Qiu raised an army of thirty thousand men. Reporting his success to the Prince of Wu, he advanced north, capturing city after city. By the time he reached Yangcheng, his forces had swelled to over a hundred thousand. He defeated the army of the commandant of the capital, securing control of the Yangcheng principality.

However, upon learning that the Prince of Wu had suffered defeat and fled, Zhou Qiu realized he could not secure victory alone. He resolved to lead his troops back to Xia’pi, but before he could reach the city, he developed a festering sore on his back and died.

There was a solar eclipse on February 30.

After the Prince of Wu abandoned his army and fled, his troops scattered, gradually surrendering to the Grand Commandant, the Marquis of Tiao, and the forces of Liang. The Prince of Wu crossed the Huai River, fled to Dantu, and sought refuge in the Kingdom of Dongyue, where he managed to rally a few thousand remaining soldiers.

Han court sent envoys to offer lavish rewards to Dongyue, which then deceived the Prince of Wu into emerging to greet the troops. As he stepped forward, they struck him down with a halberd and presented his severed head to Han as proof of his death. Meanwhile, the Crown Prince of Wu, Liu Ju, fled to the Kingdom of Minyue.

Within three months, both the Prince of Wu and the Prince of Chu were defeated. Only then did the generals recognize the wisdom of the Grand Commandant’s strategy. However, this incident deepened the rift between the Prince of Liang and the Grand Commandant, Zhou Yafu.