Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 12 Scroll 20 (continued)

The 6th year of Emperor Wu’s Yuanding Era (111 B.C. continued)

In commemorating the victory in Nanyue, sacrifices were offered to Taiyi (the Polaris) and Mother Earth, marking the first use of music and dance for the occasion.

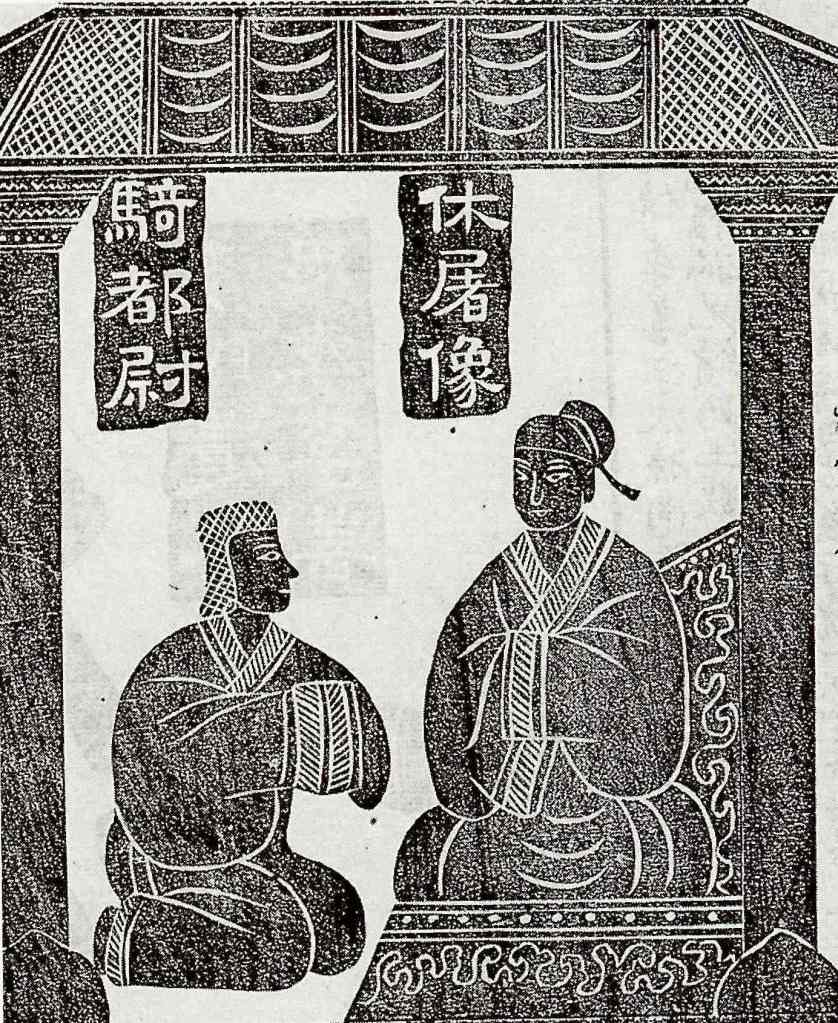

The Marquis of Chiyi, Yi, mobilized the southern troops with the intention of attacking Nanyue. However, the Lord of Julan, fearing the long journey of the troops and the potential capture of the elderly and weak by neighboring tribes’ attacks, revolted with his followers. They killed the envoy along with the Prefect of Qianwei. In response, the Han court deployed the Eight Colonels Army, composed of convicts from the Ba and Shu commanderies, to attack Nanyue, sending General of the Household Guo Chang and Wei Guang to suppress the rebellion. They executed the Lord of Julan, the Lord of Qiongdu, and the Marquis of Zuodu, pacifying the southern ethnic groups and establishing Zangke Commandery.

Initially allied with Nanyue, the Lord of Yelang saw Nanyue‘s downfall and decided to submit to the Han court. The Emperor recognized him as the King of Yelang. The Nanmeng tribes, feeling apprehensive, invited officials from the Han government and eventually established Qiongdu as the Yuesui Commandery, Zuodu as the Shenli Commandery, Nanmeng as the Wenshan Commandery, and the Baima tribe in the west of Guanghan as the Wudu Commandery.

Earlier, the King of Dongyue (Dong’ou, Minyue), Zou Yushan, petitioned the Emperor, requesting to lead eight thousand soldiers to join Louchuan General‘s expedition against Lü Jia. The troops reached Jieyang, but adverse sea winds hindered their progress, forcing them to halt. Taking advantage of this delay, they secretly aligned with Nanyue. However, when Han forces defeated Nanyue at Panyu, they did not arrive to participate.

Louchuan General Yang Pu requested permission to lead an army to attack Dongyue. However, due to the fatigue of the troops, the Emperor declined and ordered the generals to station their forces in Yuzhang and Meiling to await further orders. Upon hearing of Louchuan General‘s request to execute him, Zou Yushan rebelled, mobilizing his troops against the Han forces and holding strategic roads. General Zou Li, who was granted the title General of Annexing Han, and others led the troops. They entered the regions of Baisha, Wulin(Hangzhou), and Meiling, killing three Han Colonels.

During this time, Han court envoys, Agriculture Minister Zhang Cheng and the former Marquis of Shancheng, Liu Chi, were stationed there but dared not engage the enemy, opting instead to retreat to safer places. Both were executed for their cowardice.

The Emperor, intending to send Yang Pu out again due to his previous efforts, wrote a letter of reproach, stating: “Your merit lies only in breaking Shimen and Xunxia. You did not slay generals or seize banners on the battlefield. How can you be so conceited? You captured Panyu, treating surrendering individuals as prisoners and digging up the dead as trophies; that was one misconduct. You allowed Zhao Jiande and Lü Jia to win support from Dongyue; that was the second misconduct. Soldiers were exposed year after year, yet you, the general, did not remember their hard work. You requested to inspect the coast, returning home in government vehicles, wearing gold and silver seals, and three ribbons, boasting to your hometown folks—that was the third misconduct. Missing the deadline of return and blaming bad roads as an excuse—that was the fourth misconduct. We inquired about the price of knives in Shu, and you pretended to not know, deceiving me with false information; that was the fifth mistake.”

“When receiving orders, you did not come to Lanchi Palace, and you even remained silent the next day. Suppose your subordinate officers were asked and stayed silent, or were instructed but did not comply; what punishment would they face? With such a mindset, can you be trusted between the rivers and seas? Now that Dongyue has deeply entered our territory, can you lead your troops to redeem your misconduct?”

Frightened and filled with remorse, Yang Pu replied, “I am willing to die to atone for my mistakes!”

The Emperor dispatched Henghai General Han Yue to Gouzhang to set sail from the east; Louchuan General Yang Pu departed from Wulin(Hangzhou), and the Commandant of Capital, Wang Wenshu, came out from Meiling. Meanwhile, the leaders from the south, Gechuan General Yi and Xialai General Jia, led troops from Ruoxie and Baisha to confront Dongyue.

The Marquis of Bowang, Zhang Qian, had been granted honor and prestige for facilitating communication with the Western Regions. His subordinates vied to petition the Emperor regarding the peculiarities, advantages, and dangers of foreign countries, requesting to be dispatched as emissaries. The Emperor, aware of the distant and unenjoyable nature of these regions, listened to their requests, issued the necessary credentials, and allowed them to recruit from officials and civilians without questioning their origins. He sent them adequately prepared to broaden the horizons of the West.

However, upon their return, some of these envoys engaged in embezzlement of currency, goods, and behaviors contrary to the Emperor’s will. The Emperor, aware of these practices, sternly punished them, using severe penalties to incite redemption. Yet, they continued to request further missions, creating a cycle of persistent disregard for the law. These officials and soldiers persisted in exaggerating accounts of foreign countries; those with grandiose tales were rewarded with credentials, while those with smaller accounts were relegated to subordinate positions. Thus, individuals with no verifiable accounts zealously sought to emulate them. The envoys dispatched were often individuals of modest means, seeking to exploit their position by illicitly embezzling gifts for foreign authorities, intending to sell them for personal gain.

As a result, the people in foreign regions grew weary of Han envoys. They noticed the frivolous and overblown tales of the Han diplomats, considering the Han forces too distant to reach them. They restricted their food supplies to torment the Han envoys. This deprivation, along with accumulated grievances, led to attacks on the Han envoys by the foreign countries.

Especially in regions like Loulan and Jushi, small states located along the main route, attacks against Han diplomats like Wang Hui were severe. Additionally, the Xiongnu launched surprise attacks against them. The envoys claimed that the Western Regions were littered with cities and were vulnerable to attack.

The Emperor dispatched Fuju General, Gongsun He, with fifteen thousand cavalry, covering a distance of over two thousand li from Jiuyuan, reaching the Fuju well, and then returning. Xionghe General Zhao Ponu led over ten thousand cavalry for several thousand li, reaching the Xionghe River and then returning. Their purpose was to repel and expel the Xiongnu, preventing them from intercepting Han envoys, yet not a single Xiongnu was encountered. Following this, the commanderies of Wuwei and Jiuquan were divided to establish Zhangye and Dunhuang commanderies, with people relocated to populate these areas.

In this year, the Prime Minister of Qi, Bu Shi, was promoted to Grand Master of Censorate. After assuming his position, Bu Shi reported grievances: “It is inconvenient to let the magistrates monopolize the commerce of salt and iron tools in various commanderies and regions. They produce poor-quality items at excessively high prices. They force the people to buy these goods, causing distress. Moreover, there are high shipping costs due to exorbitant ship taxes and a scarcity of merchants.” This displeased the Emperor and contributed to his growing dissatisfaction with Bu Shi.

Sima Xiangru fell gravely ill and wrote before his passing a testament praising the Emperor’s achievements and virtues, citing omens and urging the Emperor to bestow offerings at Mount Tai. Impressed by his words and coincidentally finding a treasure cauldron, the Emperor consulted court officials and scholars to discuss the Feng-Shan ceremonies. However, as the Feng-Shan rituals were rarely performed and their procedures were not widely known, various occultists claimed, “Feng-Shan signifies immortality. Before the Yellow Emperor‘s era, these ceremonies attracted unusual phenomena and supernatural occurrences, and spoke to the gods. Even the First Emperor of Qin failed to perform it properly. If Your Majesty insists, start slowly. If there is no adverse weather, you may proceed with the ritual.”

The Emperor ordered scholars to compile texts from the “Book of Documents,” “Rites of Zhou,” and “Regulations of the Kings” to draft the procedures for the Feng-Shan ceremony. However, after several years, the rituals remained incomplete. Seeking advice, the Emperor consulted the Left Interior Minister Ni Kuan, who opined, “Offering sacrifice at Mount Tai for Heaven and offering sacrifice at Mount Liangfu for Earth are auspicious ceremonies that exalt the surname of one’s ancestors and seek auspicious signs from heaven—this is the grand ceremony of emperors. However, the essence of such offerings is not clearly expounded in the classics. The completion of the Feng-Shan ceremony should follow the will of the sage ruler and should be directed by them. This matter cannot be adequately resolved by ministers. Your Majesty has been contemplating a grand event but has allowed this issue to linger for several years, causing everyone to strive without success. Only the Son of Heaven, by establishing a harmonious center and encompassing all aspects, can harmonize the sounds of metal and resonate with the jade to align with celestial blessings, laying the foundation for ten thousand generations.”

The Emperor personally devised the rituals, incorporating elements of Confucian learning into the proceedings. When presenting the Feng-Shan ceremonial vessels specially made to the gathered scholars, some criticized them as “not in accordance with ancient practices.” Subsequently, all the scholars were dismissed from service. The Emperor followed the ancient customs, uplifted the troops’ morale and rewarded the soldiers with wine and dining before the Feng-Shan ceremony was conducted.