Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 12 Scroll 20 (continued)

The 2nd year of Emperor Wu’s Yuan’ding Era (115 B.C. continued)

After the surrender of the Hunye King to the Han Dynasty, the Han forces pursued and expelled the Xiongnu beyond the Gobi Desert. The territory east of the Salt Marsh was cleared of Xiongnu presence, and the route to the Western Regions became accessible.

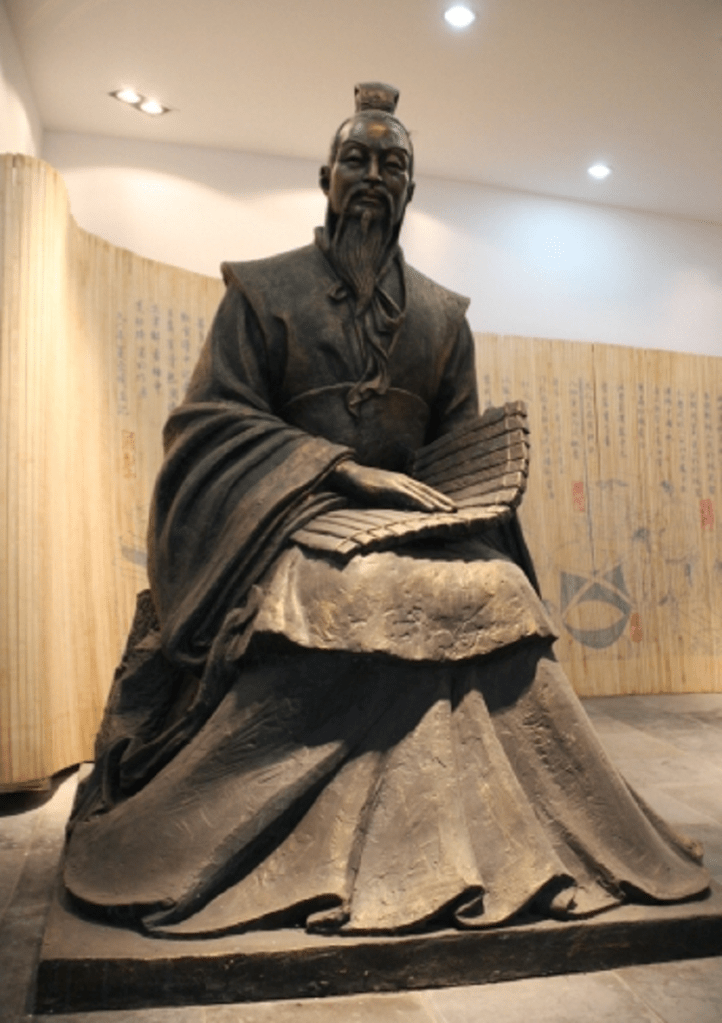

At this juncture, Zhang Qian proposed a plan: “The Wusun King, or Kunmo(Khan), was originally a vassal of the Xiongnu. Later, as his military strength grew, he refused to pay homage to the Xiongnu and, when attacked, was able to repel them. Now, with the Chanyu weakened by the Han, the former territory of Hunye King lies vacant. The barbarians are attached to their ancestral lands but are drawn by the wealth of the Han. If we offer generous bribes to the Wusun at this opportune moment and persuade them to move eastward, occupy the former territory of Hunye King, and form a fraternal alliance with the Han, the situation will be advantageous. If they answer the Han‘s call, it will be like severing the right arm of the Xiongnu. Once allied with the Wusun, the neighboring states in the Western Regions, such as Daxia(Bactria), can be brought under our influence and become our external subjects.”

The Emperor approved this proposal, appointing Zhang Qian as a General of the Household with three hundred men, each with two horses, and tens of thousands of cattle and sheep. He was supplied with substantial amounts of gold, coins, and silk, accompanied by numerous assistant ambassadors bearing royal insignia, and sent as a representative to neighboring kingdoms along the way.

Upon Zhang Qian‘s arrival at Wusun, the Kunmo(Khan), Wusun King, received him with insolence. Zhang Qian conveyed the message from the Emperor: “If the Wusun people relocate eastward to their former territory, the Han will send a princess to be your wife, establish a fraternal bond, and together resist the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu will no longer pose a threat.”

The Wusun, distant from the Han and unaware of its greatness, had long been subservient to the Xiongnu. Furthermore, they lived in close proximity to the Xiongnu, and their ministers, fearful of the Xiongnu, were reluctant to make any move. Despite Zhang Qian‘s prolonged stay, he was unable to make inroads with them.

Therefore, he dispatched his assistant envoys to neighboring kingdoms such as Dayuan(Ferghana), Kangju(Sogdia), Greater Yuezhi(Sakas), Daxia(Bactria), Anxi(Parthian), Juandu(India), Khotan, and others. The Wusun provided interpreters and guides to accompany Zhang Qian on his return journey, sending dozens of people and several dozen horses as a token of gratitude, as well as to gather information about the Han‘s strength and resources.

In that year, upon Zhang Qian‘s return, he was appointed as the Grand Usher. Over the following years, assistant ambassadors sent by Zhang Qian to communicate with the states of Daxia and others gradually returned, some accompanied by diplomats from those kingdoms. Thus, communication between the Western Regions and the Han began to open up.

The Western Regions consist of a total of thirty-six nations, divided by great mountains running from north to south, with a river flowing through the center. The region spans over six thousand li from east to west and more than a thousand li from north to south. To the east, it connects to Han territory via Yumen Pass and Yangguan Pass, and to the west, it is bordered by the Onion Range (Pamir Mountains). The river in this region, the Tarim River, originates from two sources: one from the Onion Range and the other from the Southern Mountains(Kunlun Mountains) of Khotan. The two sources merge and flow eastward into the Salt Marsh (Lop Nur), located about three hundred li from Yumen Pass and Yangguan Pass.

From Yumen Pass and Yangguan Pass, there are two routes in the Western Regions. The first follows the north side of the Southern Mountains near Shanshan(f.k.a. Loulan), running west along the river to Shache (Yarkant), forming the southern route. Beyond the southern route, it crosses the Onion Range (Pamir Mountains), leading to the Greater Yuezhi and Anxi. The second route originates from the royal court of the Front Cheshi (Jushi) King, proceeding north along the Northern Mountains (Tianshan Mountains) and the river (Tarim River) to Shule, constituting the northern route. Beyond the northern route, it crosses the Onion Range, leading to Dayuan, Kangju, and Yancai (Sogdiana).

All these regions were under the control of the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu Rizhu King of the Western Regions established a Commandant of Minions who oversaw the Western Regions. They resided in Yanqi (Karasahr), Weixu, and Yuli (Lop Nur county), levying taxes from the various kingdoms and gaining wealth from this area.

As the Wusun King declined to return east, the Han established Jiuquan Commandery in the former territory of the Hunye King, gradually relocating people to settle there. Later, they also established Wuwei Commandery to sever communication routes between the Xiongnu and the Qiang tribes.

The Emperor acquired a blood-sweat horse (Akhal-Teke) from the Dayuan kingdom, which he greatly adored and named “Heavenly Horse.” Envoys were sent along various routes to acquire more horses of the same breed. When these envoys were dispatched to foreign countries, their entourages were large, often numbering several hundred or more people. At that time, people carried grand gifts in the style of Marquis Bowang (Zhang Qian), displaying magnanimity and respect. However, over time, these practices became more routine, and as a result, both the envoy’s entourage and the amount of gifts dwindled.

The Han regularly dispatched multiple envoys annually, with over ten missions in some years and five or six in others. Distant missions took about eight or nine years to complete, while those to nearer regions took several years to return.

The 3rd year of Emperor Wu’s Yuan’ding Era (114 B.C.)

In winter, the Hangu Pass was relocated from Hongnong to Xin’an.

In the spring, on January 27, a fire broke out in the Yangling Garden (the Mausoleum of Emperor Jing).

In April, during the summer, there was rain and hail. More than ten commanderies and regions to the east of Hangu Pass suffered from famine, causing people to resort to cannibalism.

Prince Xian of Changshan, Liu Shun, passed away. His son, Liu Bo, succeeded him. Liu Bo was accused of neglecting Prince Xian during his illness and showing disrespect during the mourning period, which led to his demotion to Fangling. A month later, the Emperor bestowed the title of Prince of Zhen’ding upon Liu Ping, another son of Prince Xian, and made Changshan into a commandery. As a result, all Five Sacred Mountains came under the Emperor’s direct administration.

Liu Yi, the Prince of Dai, was relocated and made the Prince of Qinghe.

During this year, Xiongnu Chanyu Yizhixie passed away, and his son, Wuwei Chanyu, succeeded him.