Comprehensive Reflections to Aid in Governance

By Sima Guang

Translated By Yiming Yang

Annals of Han Book 16 Scroll 24 (continued)

The 1st year of Emperor Zhao’s Yuanping Era (74 B.C. continued)

After the deposition of the Prince of Changyi, the choice of successor was debated among the senior ministers, including Huo Guang and Zhang Anshi. As no decision was yet reached, Bing Ji submitted a memorial to Huo Guang, saying:

“Grand General, you served Emperor Wu, bearing the charge of raising his heir from infancy, entrusted with the care of the entire realm. When Emperor Zhao passed away untimely, leaving no heir, fear and unease spread throughout the empire. On the day of the funeral, for the sake of the great enterprise, a successor was hastily chosen; but perceiving the choice amiss, he was deposed for the greater cause, and all under Heaven assented. At this juncture, the fate of the state, the ancestral temples, and the lives of the people depend upon your judgment.

“I have listened to the voices of the people and observed the discourse regarding the princes of the imperial clan, yet have heard no worthy name outside the court. Meanwhile, within the harem by posthumous decree, the Imperial Great-Grandson Liu Bingyi has been fostered, reared under the care of the inner palace and his maternal great grandmother. When I once served at the commandery prison, I beheld him as a child. Now he is eighteen or nineteen years of age, well versed in the Confucian classics, of comely talent and serene bearing.

“I earnestly entreat the General, considering the highest righteousness, to seek the judgment of the tortoise oracle; if it proves auspicious, then let him be appointed attendant to the Empress Dowager and enter the palace, so that all under Heaven may behold him. Then, with the world’s gaze upon him, the final decision may be made, to the blessing of the empire.”

Du Yannian also discerned the virtue of the Imperial Great-Grandson, and urged Huo Guang and Zhang Anshi to establish him as successor.

In July of autumn, Huo Guang, seated in the court, convened with the Chancellor Yang Chang and the ministers to deliberate, and together they memorialized, saying: “The Great-Grandson of Emperor Wu, Liu Bingyi, is now eighteen years of age. He has been instructed in the Book of Songs, the Analects, and the Classic of Filial Piety. He himself practices frugality, kindness, and benevolence. He is fit to succeed Emperor Zhao, to continue the sacrifices of the ancestral temples, and to nurture the people. We memorialize this, even at the cost of our lives.”

The Empress Dowager decreed: “It is permitted.”

Huo Guang sent the Minister of the Imperial Clan, Liu De, to the residence of the Imperial Great-Grandson at Shangguanli, where he was bathed and robed in imperial garments. The Grand Coachman dispatched a light carriage to escort him to the Ministry of the Imperial Clan.

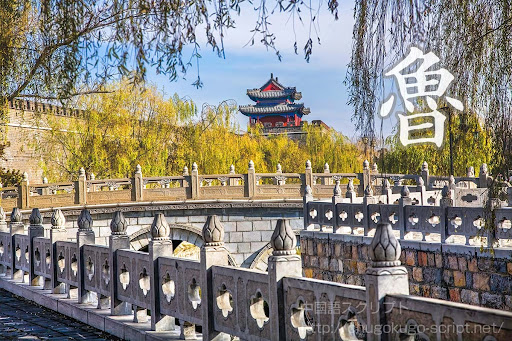

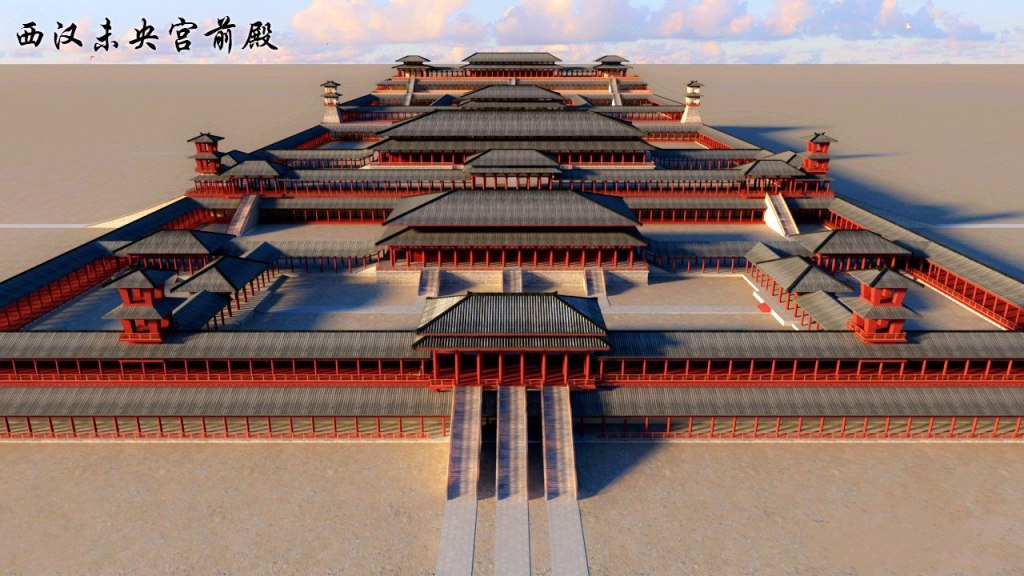

On July 25, Liu Bingyi entered Weiyang Palace, audience with the Empress Dowager, and was ennobled as Marquis of Yangwu.

Afterward the court officials presented the imperial seal and ribbon, and he was formally enthroned as Emperor. He went to offer sacrifice at the Temple of Emperor Gaozu, and honored the Empress Dowager with the title of Grand Empress Dowager.

The Imperial Censor Yan Yannian accused Huo Guang, submitting a memorandum, saying: “General Huo has deposed and established an emperor of his own will, not in accord with the rites of a loyal minister. This is not fitting.” Though the charge was dismissed, the officials of the court ever after revered and feared Yan Yannian.

On August 5, Yang Chang, Marquis of Anping, died.

In September, a general amnesty was proclaimed throughout the empire.

On September 5, Cai Yi was appointed Chancellor.

Earlier, the daughter of Xu Guanghan had been wedded to the Imperial Great-Grandson Liu Bingyi. After one year she bore him a son, Liu Shi. Within a few months thereafter, the Great-Grandson became Emperor, and the house of Xu grew in influence. At that time the General Huo Guang had a young daughter, kin to the Empress Dowager. When the choice of an empress was under discussion, some secretly inclined toward Huo Guang’s daughter, but none dared to speak openly.

The Emperor thereupon issued a decree, seeking for the old sword he had carried in his obscurity. The wise among the ministers discerned his inkling, and proposed the daughter of Xu Guanghan as the Empress. On November 9, Consort Xu(Jieyu[Lady of Handsome Fairness]) was established as Empress. Later, Huo Guang judged Xu Guanghan, who had been punished by castration, unfit to hold the title of a head of state. After one year, he was enfeoffed as Lord of Changcheng.

The Grand Empress Dowager returned to dwell in Changle Palace, where guards were stationed for the first time.

The 1st year of Emperor Xuan’s Benshi Era (73 B.C.)

In the spring, an imperial decree ordered the ministers to deliberate on the merit of securing the imperial succession and continuing the ancestral sacrifices. The Grand General Huo Guang was augmented with a fief of seventeen thousand households, in addition to his former twenty thousand. The Chariot and Cavalry General, Zhang Anshi, Marquis of Fuping, together with ten others of lesser rank, all received increases of fief. Five men were enfeoffed as marquises, and eight were created Inner Marquises.

The Grand General Huo Guang prostrated himself, humbly petitioning to return the affairs of state to the Emperor, but the Emperor refused, insisting that he continued his duty. He decreed that all matters must first be presented to Huo Guang for judgment, and only then submitted for imperial sanction.

From the time of Emperor Zhao, Huo Guang’s son Huo Yu, and his elder brother Huo Qubing’s grandson, Huo Yun, both served as Generals of the Household. Huo Yun’s younger brother, Huo Shan, was Commandant of Chariots and Privy Counselor, commanding troops of the northern and southern tribes. Two sons-in-law of Huo Guang held the posts of Guard Commandants of the Eastern and Western Palaces. His kinsmen by blood and marriage—brothers, sons-in-law, and grandsons—crowded the court, filling the offices of administrators, grandees, commandants, and palace liaisons. Thus they formed a tightly bound faction.

As the power of Huo Guang grew, especially after the deposition of the Prince of Changyi, his authority became ever more preeminent. In court audiences the Emperor humbled his bearing, withdrew his countenance, and displayed undue deference toward him.

On April 10, in summer, there was an earthquake.

In May, phoenixes gathered in Jiaodong and Qiansheng. A general amnesty was proclaimed throughout the empire, and the collection of land taxes and levies was suspended.

In June, an imperial decree was issued, saying: “The former Crown Prince, who lies at rest in Hu County, has neither been granted a posthumous name nor received annual sacrifice. Let there be discussion on bestowing a posthumous title and establishing an estate for his tomb garden.”

The officials in charge memorialized, saying: “According to the rites, when one inherits the title of a man, he must be accounted his son; thus the sacrifices to his true parents must cease, in order to honor the ancestral line. Now Your Majesty, as the descendant of Emperor Zhao, inherits the sacrifices of the imperial temple. We propose that the posthumous title of Your Majesty’s true(biological) father be Prince Dao, and of Your Majesty’s true(biological) mother be Queen Dao. Further, that the former Crown Prince, Your Majesty’s true grandsire, be posthumously named Crown Prince Li, and his consort, Lady Shi, be styled Madame Li.”

All these were accordingly reburied with their proper honors.